Majority quorum requires floor(N/2)+1 nodes to agree. For 5 nodes, quorum is 3. The W+R>N formula ensures consistency: if Write quorum + Read quorum > Total nodes, at least one read node has the latest write. Odd node counts (3, 5, 7) are preferred to prevent ties during network splits.

You have five servers running your e-commerce database. Orders are flowing in. A customer places an order at 10:15:03 AM. Server 1 records it. Servers 2 and 3 get the update. But servers 4 and 5? They were busy handling other requests and haven’t received the update yet.

Now the customer refreshes their order history page. The request lands on server 5. It has no record of the order. The customer panics: “Where’s my order? Did I get charged for nothing?”

This is the distributed systems nightmare. When data lives on multiple servers, how do you make sure everyone agrees on what’s true?

The answer is a pattern called Majority Quorum, and it’s the reason your distributed databases don’t descend into chaos.

The Problem: When Servers Disagree

Let’s start with why this is hard.

The Three Generals Problem

Imagine three generals in ancient times, each commanding an army on different hilltops. They need to coordinate an attack. If all three attack together, they win. If only one or two attack, they lose.

The generals communicate by sending messengers. But messengers can be captured. Messages can be delayed. How do the generals coordinate?

graph TD

subgraph "Hill A"

A[General A]

end

subgraph "Hill B"

B[General B]

end

subgraph "Hill C"

C[General C]

end

A -->|"Attack at dawn?"| B

B -->|"Agreed"| A

A -->|"Attack at dawn?"| C

C -->|"Message lost"| X[Enemy Territory]

style X fill:#ffcdd2

General A thinks everyone agreed. General C never got the message. What happens at dawn?

This is exactly what happens in distributed systems. Servers send messages. Messages get delayed or lost. Servers crash. Networks partition. And somehow, the system needs to keep making decisions.

The Solution: Majority Rules

Here’s the insight that changes everything: If a majority agrees, we have a decision.

Think about it. In a room of 5 people, if 3 agree on pizza for dinner, you’re getting pizza. The 2 who wanted sushi can object, but they’re outnumbered. The decision is made.

More importantly, you can never have two different majorities. If 3 people agree on pizza, the remaining 2 can’t form a majority for sushi. There’s only one winning group.

This is the Majority Quorum pattern.

The Math

For a cluster of N nodes, the quorum size is:

1

Quorum = floor(N/2) + 1

Or in simpler terms: more than half.

| Cluster Size | Quorum Size | Can Tolerate Failures |

|---|---|---|

| 3 nodes | 2 nodes | 1 failure |

| 5 nodes | 3 nodes | 2 failures |

| 7 nodes | 4 nodes | 3 failures |

| 9 nodes | 5 nodes | 4 failures |

Notice the pattern: to tolerate F failures, you need 2F + 1 nodes.

Why? Because even if F nodes fail, you still have F + 1 nodes left, which is still a majority.

How Majority Quorum Works

Let’s trace through what happens when you write and read data in a quorum-based system.

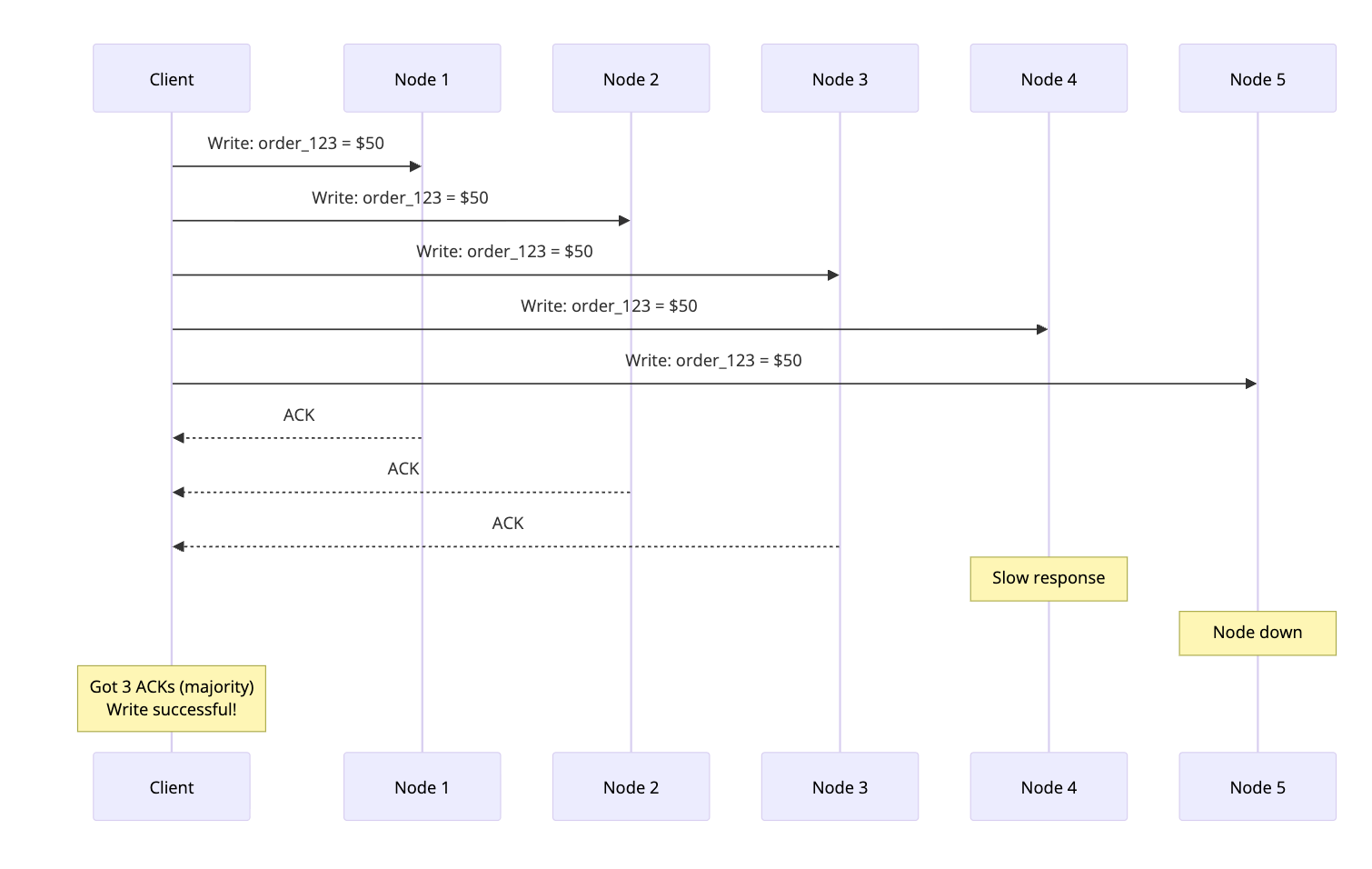

Write Operations

When a client writes data, the system sends the write to all nodes but only waits for a majority to acknowledge.

The client doesn’t wait for nodes 4 and 5. Once 3 nodes confirm, the write is successful. This is the write quorum in action.

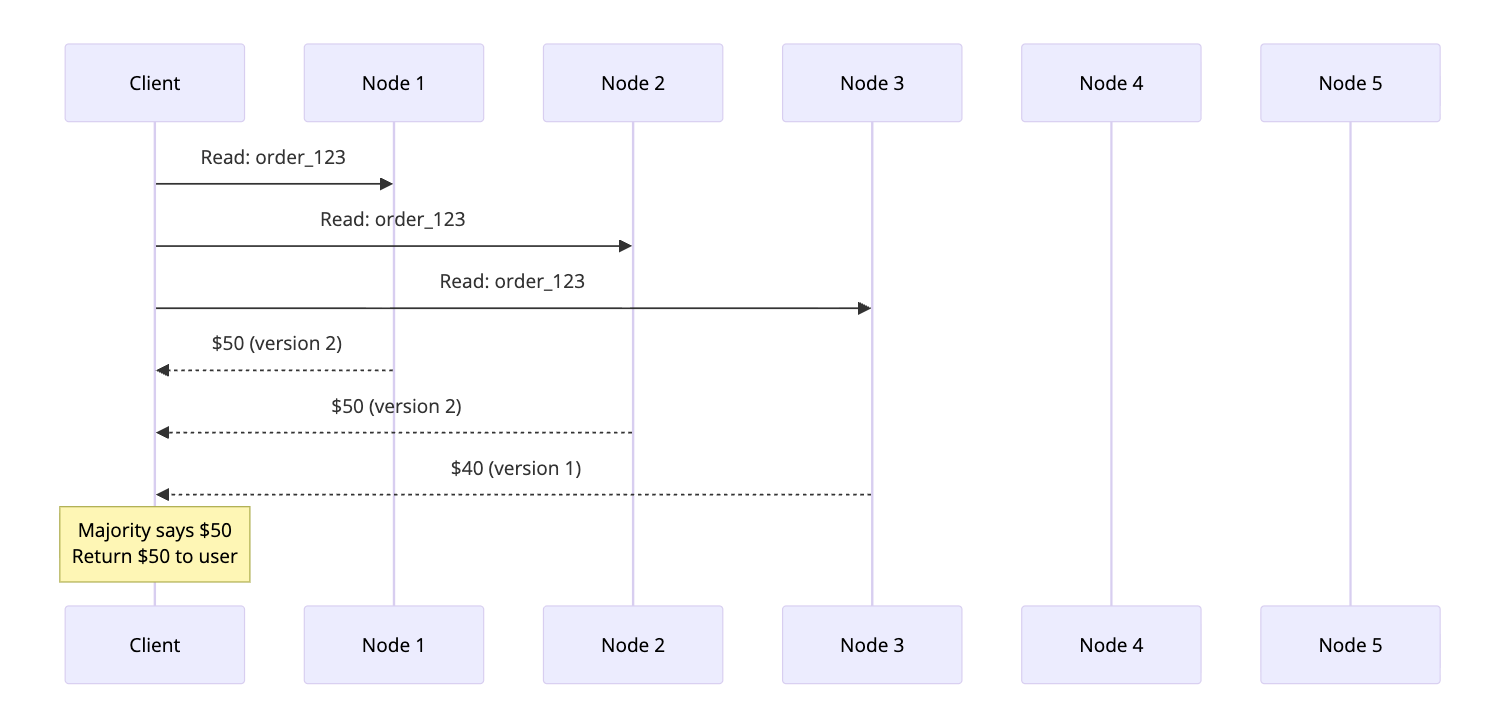

Read Operations

For reads, the client queries multiple nodes and takes the most recent value.

Node 3 had stale data, but the majority had the correct value. The client gets the right answer.

The Overlap Guarantee

Here’s the key insight: if you write to a majority and read from a majority, at least one node will have the latest data.

graph TB

subgraph "5-Node Cluster"

N1[Node 1]

N2[Node 2]

N3[Node 3]

N4[Node 4]

N5[Node 5]

end

subgraph "Write Quorum (3 nodes)"

W1[Node 1]

W2[Node 2]

W3[Node 3]

end

subgraph "Read Quorum (3 nodes)"

R1[Node 2]

R2[Node 3]

R3[Node 4]

end

O[Node 2 & 3 overlap<br/>They have the latest data]

style O fill:#c8e6c9

Any two majorities in a group must overlap. That overlap node guarantees you read the latest write.

The Read/Write Formula

Different systems tune their quorums differently. The key constraint is:

1

W + R > N

Where:

- W = Write quorum (nodes that must acknowledge a write)

- R = Read quorum (nodes to query for a read)

- N = Total nodes

As long as this inequality holds, you’re guaranteed to read your own writes.

Different Configurations

Strong Consistency (W=3, R=3, N=5)

- Every write waits for 3 nodes

- Every read queries 3 nodes

- Always get latest data

- Slower operations

Read-Heavy Workload (W=3, R=2, N=5)

- Writes still need majority (3)

- Reads only need 2 nodes

- Reads are faster

- Still consistent (3 + 2 > 5)

Write-Heavy Workload (W=2, R=3, N=5)

- Writes need only 2 nodes

- Reads must query 3 nodes

- Writes are faster

- Still consistent (2 + 3 > 5)

graph LR

subgraph "Strong Consistency"

A["W=3, R=3<br/>Slow but always consistent"]

end

subgraph "Read Optimized"

B["W=3, R=2<br/>Fast reads, slower writes"]

end

subgraph "Write Optimized"

C["W=2, R=3<br/>Fast writes, slower reads"]

end

style A fill:#e3f2fd

style B fill:#e8f5e9

style C fill:#fff3e0

Why Odd Numbers Matter

Ever notice that distributed systems often run on 3, 5, or 7 nodes? There’s a reason.

Consider a 4-node cluster:

- Quorum = floor(4/2) + 1 = 3

- You can tolerate only 1 failure

Now consider a 5-node cluster:

- Quorum = floor(5/2) + 1 = 3

- You can tolerate 2 failures

Both require 3 nodes for quorum, but 5 nodes gives you better fault tolerance. The extra node is “free” resilience.

With even numbers, you also risk tie situations:

graph TB

subgraph "Network Partition"

subgraph "Partition A"

A1[Node 1]

A2[Node 2]

end

subgraph "Partition B"

B1[Node 3]

B2[Node 4]

end

end

X[Neither side has majority<br/>System is stuck]

style X fill:#ffcdd2

With 4 nodes split 2-2, neither side can form a quorum. The system halts. With 5 nodes, one side will always have 3 and can continue.

Rule of thumb: Always use odd numbers for your cluster size.

Real-World Examples

Apache Cassandra: Tunable Consistency

Cassandra lets you choose your consistency level per query. Here’s what happens when you write with QUORUM consistency:

1

2

3

4

-- Write with quorum consistency

INSERT INTO orders (id, amount, status)

VALUES (123, 50.00, 'pending')

USING CONSISTENCY QUORUM;

Behind the scenes:

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Coordinator

participant Replica1

participant Replica2

participant Replica3

Client->>Coordinator: INSERT order_123

Coordinator->>Replica1: Write

Coordinator->>Replica2: Write

Coordinator->>Replica3: Write

Replica1-->>Coordinator: ACK

Replica2-->>Coordinator: ACK

Note over Coordinator: 2/3 replicas confirmed<br/>Quorum achieved

Coordinator-->>Client: Success

Replica3-->>Coordinator: ACK (later)

Cassandra offers these consistency levels:

| Level | What it means |

|---|---|

| ONE | Wait for 1 replica |

| QUORUM | Wait for majority |

| ALL | Wait for all replicas |

| LOCAL_QUORUM | Majority in local data center |

Most production systems use LOCAL_QUORUM for writes and LOCAL_QUORUM for reads. This gives you consistency within a data center while tolerating cross-datacenter latency.

ZooKeeper: Leader Election

ZooKeeper uses quorum for something even more fundamental: electing a leader.

When ZooKeeper starts, nodes vote for a leader:

sequenceDiagram

participant N1 as Node 1

participant N2 as Node 2

participant N3 as Node 3

participant N4 as Node 4

participant N5 as Node 5

Note over N1,N5: Election starts

N1->>N2: Vote for N5 (highest ID)

N1->>N3: Vote for N5

N2->>N1: Vote for N5

N2->>N3: Vote for N5

N3->>N1: Vote for N5

N3->>N2: Vote for N5

Note over N5: Received majority votes<br/>Becomes Leader

N5->>N1: I am the leader

N5->>N2: I am the leader

N5->>N3: I am the leader

N5->>N4: I am the leader

The leader is elected by quorum. All writes go through the leader. The leader only acknowledges a write when a quorum of followers confirm it.

This is why ZooKeeper clusters are always odd-sized. Their documentation explicitly recommends 3 or 5 nodes.

etcd and Kubernetes: Raft Consensus

etcd, the brain of Kubernetes, uses the Raft consensus algorithm. Raft relies heavily on majority quorum. (For a deeper look at consensus algorithms, see Paxos: The Democracy of Distributed Systems.)

Every Kubernetes cluster state change (pod created, service updated, deployment scaled) goes through etcd:

sequenceDiagram

participant API as API Server

participant E1 as etcd 1 (Leader)

participant E2 as etcd 2 (Follower)

participant E3 as etcd 3 (Follower)

API->>E1: Write request

E1->>E2: Replicate log entry

E1->>E3: Replicate log entry

E2-->>E1: ACK

E3-->>E1: ACK

Note over E1: Majority confirmed<br/>Commit the write

E1-->>API: Success

When the leader commits a log entry, it must be replicated to a majority first. This is why production Kubernetes clusters run 3 or 5 etcd nodes.

Fun fact: Kubernetes can survive losing minority of etcd nodes. Lose 2 out of 5, and your cluster keeps running. Lose 3, and it freezes until you recover nodes.

The Split-Brain Problem

The biggest threat to distributed systems is the split-brain scenario. This happens when a network partition divides your cluster, and both sides think they’re in charge.

graph TB

subgraph "Before Partition"

A1[Node 1]

A2[Node 2]

A3[Node 3]

A4[Node 4]

A5[Node 5]

end

subgraph "After Partition"

subgraph "Partition A"

B1[Node 1]

B2[Node 2]

B3[Node 3]

end

subgraph "Partition B"

B4[Node 4]

B5[Node 5]

end

end

C[Partition A has 3 nodes = quorum<br/>Can continue operations]

D[Partition B has 2 nodes = no quorum<br/>Must stop accepting writes]

style C fill:#c8e6c9

style D fill:#ffcdd2

Majority quorum prevents split-brain by design. Only one partition can have a majority. The minority partition must stop accepting writes.

This is a tradeoff. The minority partition becomes unavailable. But the alternative (two partitions making conflicting updates) is worse. You’d end up with divergent data that’s nearly impossible to reconcile.

This is the core tension in the CAP theorem. Majority quorum chooses Consistency over Availability during a partition.

Practical Considerations

Latency Impact

Quorum operations are only as fast as the slowest node in your quorum.

gantt

dateFormat X

axisFormat %L ms

section Node 1

Response :done, 0, 50

section Node 2

Response :done, 0, 30

section Node 3

Response :done, 0, 200

section Quorum

Wait for 2 fastest :crit, 0, 50

If you need 2 out of 3 nodes, you wait for the 2nd response. In this case, 50ms instead of 200ms. The slowest node doesn’t hurt you (unless all your nodes are slow).

Optimization: Place nodes in different availability zones but same region. You get fault isolation without cross-region latency.

Monitoring Quorum Health

In production, monitor these metrics:

- Quorum available: Can you reach a majority of nodes?

- Write latency percentiles: Are quorum writes slowing down?

- Replication lag: How far behind are non-quorum nodes?

- Node health: How many nodes are actually healthy?

Set alerts when you’re close to losing quorum:

1

2

3

Alert: Only 3 of 5 nodes healthy

Severity: Warning

Message: One more node failure will break quorum

This gives you time to investigate before an outage.

Handling Node Failures

When a node fails, the system keeps running as long as quorum is maintained. But you should:

- Replace failed nodes quickly: Running at minimum quorum is risky

- Don’t add too many nodes at once: Large membership changes can destabilize the cluster

- Use rolling restarts: Never restart more than one node at a time

Some systems like etcd have explicit membership change protocols to handle this safely.

When Quorum Gets Tricky

Geographic Distribution

Quorum across data centers introduces latency challenges:

graph LR

subgraph "US East"

E1[Node 1]

E2[Node 2]

end

subgraph "US West"

W1[Node 3]

end

subgraph "Europe"

EU1[Node 4]

EU2[Node 5]

end

E1 -.->|80ms| W1

E1 -.->|120ms| EU1

W1 -.->|180ms| EU1

If quorum requires cross-region communication, every write pays the latency cost. Solutions include:

- Local quorum: Achieve quorum within a region first, replicate asynchronously

- Witness nodes: Place small witness nodes in a third location to break ties

- Leader placement: Put the leader in the region with most traffic

Dynamic Membership

Adding or removing nodes from a quorum cluster is tricky. If you’re not careful, you can end up with two groups both thinking they have quorum.

Safe approach (used by Raft):

- Propose the membership change as a log entry

- Wait for it to commit (requires current quorum)

- New configuration takes effect

- Old members step down if no longer part of cluster

Never jump directly from 3 to 5 nodes. Add one at a time and let the cluster stabilize.

When to Use Majority Quorum

Use quorum-based systems when:

- You need strong consistency

- You can tolerate some unavailability during partitions

- Your cluster size is reasonably small (3 to 7 nodes typically)

- Operations can wait for multiple responses

Avoid quorum when:

- Availability is more important than consistency

- You have very large clusters (quorum of 50 nodes is slow)

- Single-node latency is already a bottleneck

- You’re doing read-heavy workloads where eventual consistency is acceptable

The Tradeoffs

| Aspect | With Quorum | Without Quorum |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Strong | Eventual |

| Availability | Reduced during partitions | Higher |

| Latency | Higher (wait for majority) | Lower (single node) |

| Complexity | Moderate | Lower |

| Split-brain risk | Eliminated | Possible |

Wrapping Up

Majority Quorum is one of the most fundamental patterns in distributed systems. It solves the core problem of getting multiple servers to agree without a central authority.

The key insights:

- Majority agreement prevents conflicts: Two majorities always overlap

- Odd numbers maximize fault tolerance: 5 nodes tolerates 2 failures with same quorum as 4

- W + R > N guarantees consistency: Your reads will see your writes

- Quorum trades availability for consistency: Minority partitions stop accepting writes

- Real systems use quorum everywhere: Cassandra, ZooKeeper, etcd, Raft

Understanding quorum is essential because it shows up in so many places. Leader election, log replication, distributed transactions, and consensus algorithms all build on this foundation.

The next time your database says “quorum achieved,” you’ll know exactly what it means: more than half agreed, and that’s enough to make a decision.

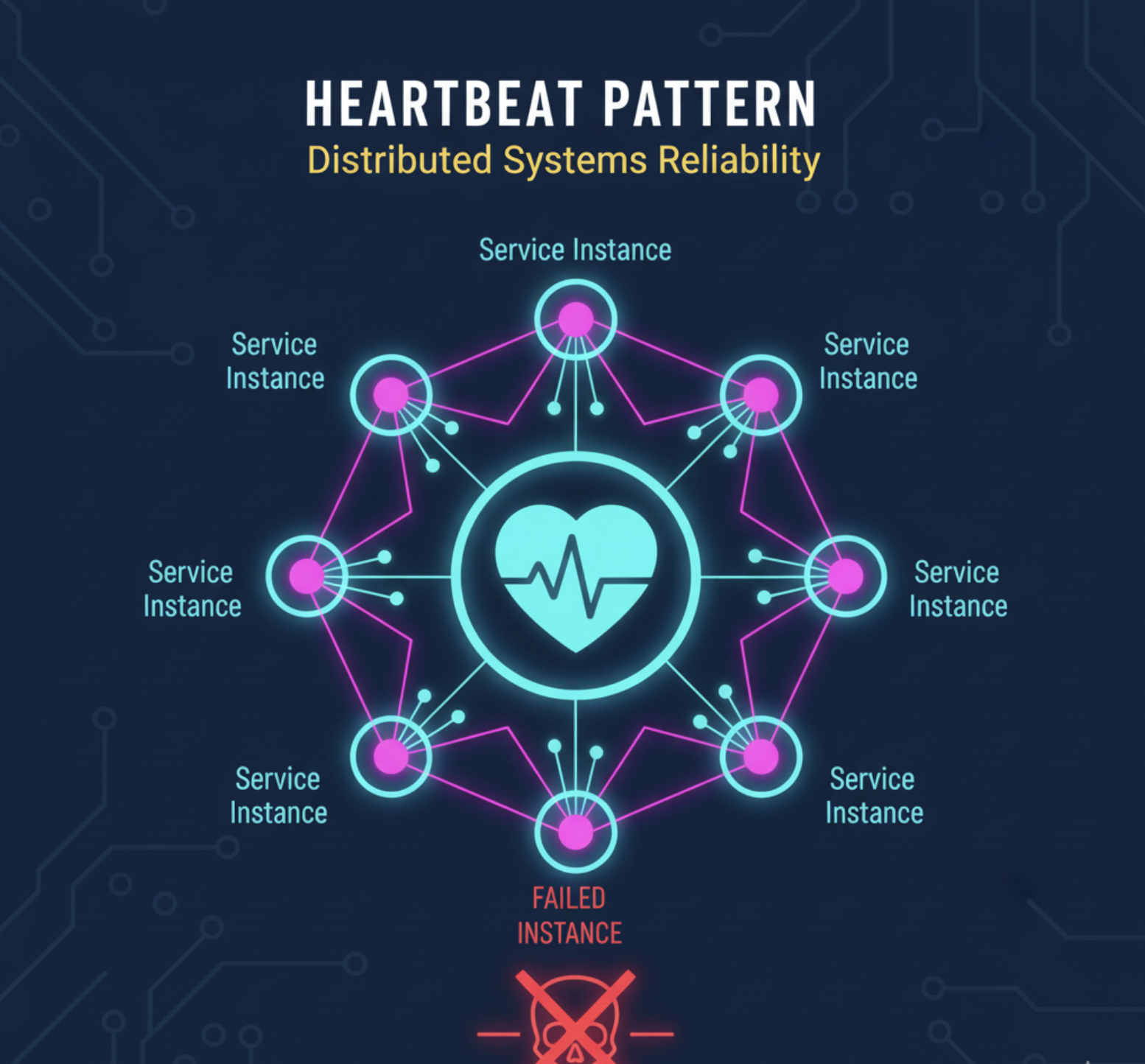

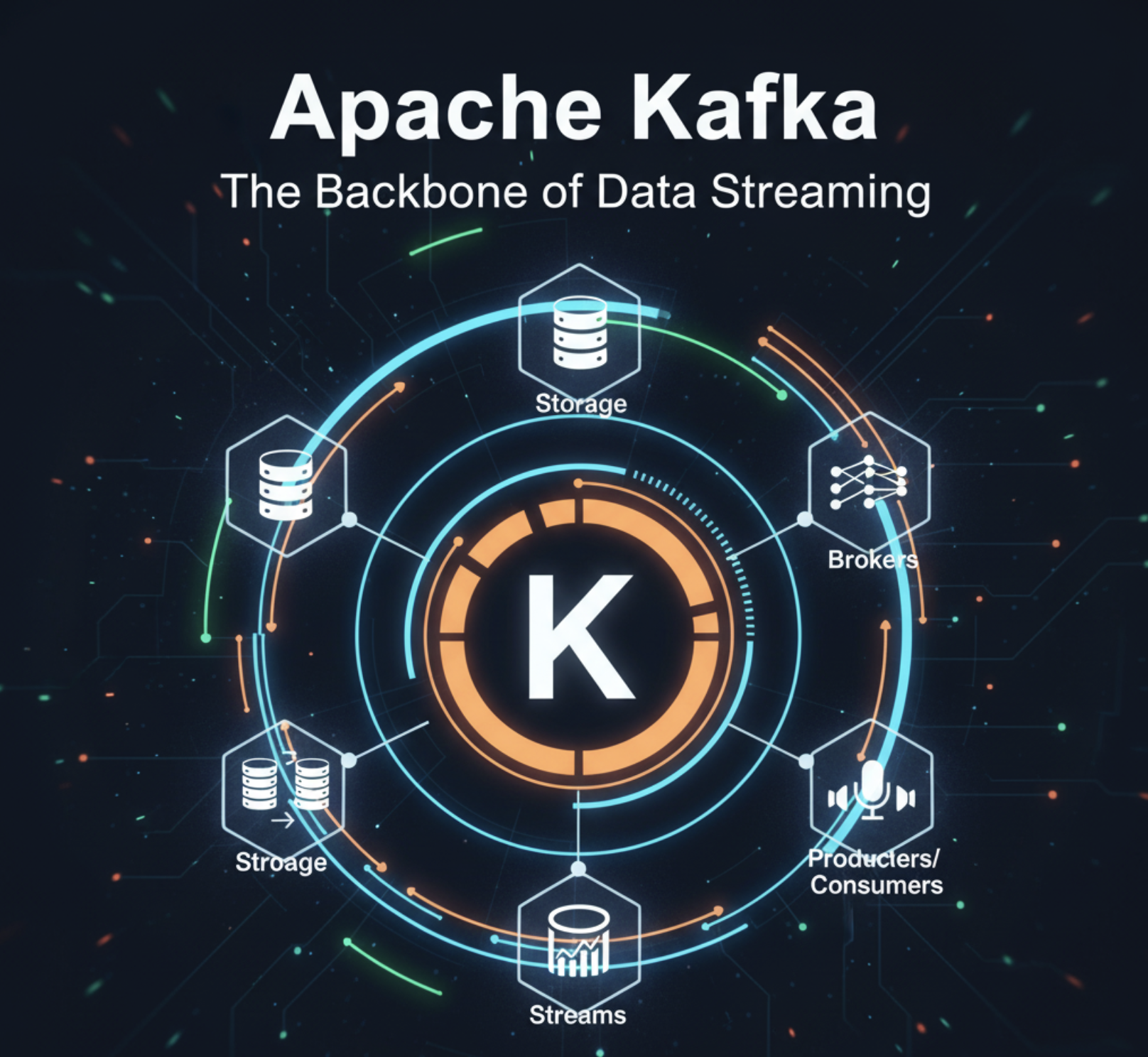

For more on distributed systems patterns, check out Replicated Log, Gossip Dissemination, Heartbeat: Detecting Failures, Paxos Consensus Algorithm, Write-Ahead Log, and Two-Phase Commit. Building high-availability systems? See How Kafka Works for durable message queuing.

References: Martin Kleppmann’s Designing Data-Intensive Applications, Raft Consensus Algorithm, Apache Cassandra Documentation, etcd Design