Five main strategies: Cache-Aside (app manages cache, most common), Read-Through (cache fetches on miss), Write-Through (sync to both), Write-Behind (cache first, async to DB), Write-Around (bypass cache on writes). LRU eviction for most cases. Start with Cache-Aside + Redis. Use Write-Through for critical consistency.

Caching is not optional. If you are building any application that needs to scale, you will deal with caching. But here is the thing: most developers throw Redis at the problem without thinking about which caching strategy fits their use case.

The result? Cache inconsistencies, stale data bugs, or systems that are slower than they should be.

This guide covers the core caching strategies that every backend developer needs to understand. No fluff, just the patterns, when to use them, and the tradeoffs you should know about.

Why Caching Matters

Before diving into strategies, let us quickly establish why caching exists.

The Problem: Database queries are slow. Even with indexes, reading from disk takes milliseconds. At scale, those milliseconds add up to seconds.

The Solution: Keep frequently accessed data in memory. Memory access is 100,000 times faster than disk access.

| Storage Type | Access Time | Relative Speed |

|---|---|---|

| L1 Cache (CPU) | 0.5 ns | 1x |

| RAM | 100 ns | 200x slower |

| SSD | 100 μs | 200,000x slower |

| HDD | 10 ms | 20,000,000x slower |

| Network DB | 50 ms+ | 100,000,000x slower |

A cache hit that takes 1ms vs a database query that takes 50ms makes a huge difference when you are handling thousands of requests per second.

The Six Caching Strategies

There are six main caching strategies. Each has its place depending on your read/write patterns and consistency requirements.

| Strategy | How It Works | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Cache-Aside | Application manages cache directly | General purpose, most control |

| Read-Through | Cache fetches from DB on miss | Read-heavy workloads, simpler code |

| Write-Through | Writes go to cache and DB synchronously | Consistency critical (financial data) |

| Write-Behind | Writes to cache first, async to DB | Write-heavy, high throughput |

| Write-Around | Writes bypass cache, go to DB only | Write-once data (logs, events) |

| Refresh-Ahead | Proactively refresh before expiry | Predictable access patterns |

Let us dive into each one.

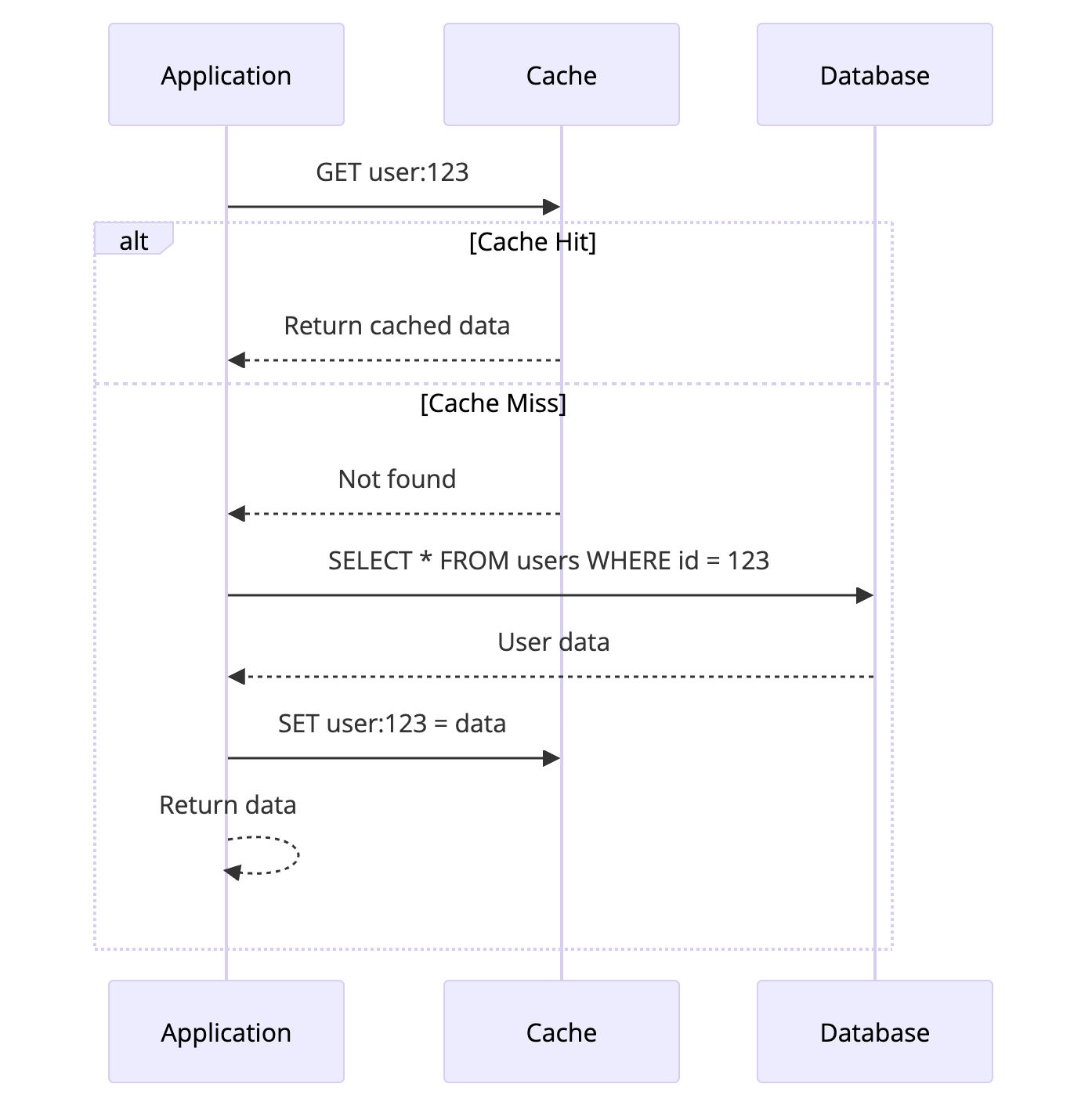

1. Cache-Aside (Lazy Loading)

Cache-Aside is the most common caching pattern. The application code is responsible for managing the cache.

How It Works

- Application checks the cache first

- If data exists (cache hit), return it

- If data does not exist (cache miss), query the database

- Store the result in cache for future requests

- Return the data

Code Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

def get_user(user_id):

# Step 1: Check cache first

cache_key = f"user:{user_id}"

cached_user = cache.get(cache_key)

if cached_user:

return cached_user # Cache hit

# Step 2: Cache miss - query database

user = db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?", user_id)

# Step 3: Populate cache for next time

cache.set(cache_key, user, ttl=3600) # 1 hour TTL

return user

def update_user(user_id, data):

# Update database

db.execute("UPDATE users SET ... WHERE id = ?", data, user_id)

# Invalidate cache

cache.delete(f"user:{user_id}")

When to Use Cache-Aside

Read-heavy workloads where data is read more often than written

You need fine-grained control over what gets cached

Cache failures should not break the application (graceful degradation)

General purpose caching when you are not sure which pattern to use

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Simple to implement | Application must manage cache |

| Cache failure does not break reads | First request is always slow (cold cache) |

| Only caches data that is actually read | Potential for stale data |

| Works with any cache backend | Cache and DB can get out of sync |

Real World Usage

Facebook uses Cache-Aside with Memcached for user profile data. Applications check Memcached first, fall back to MySQL on miss, and populate the cache after fetching.

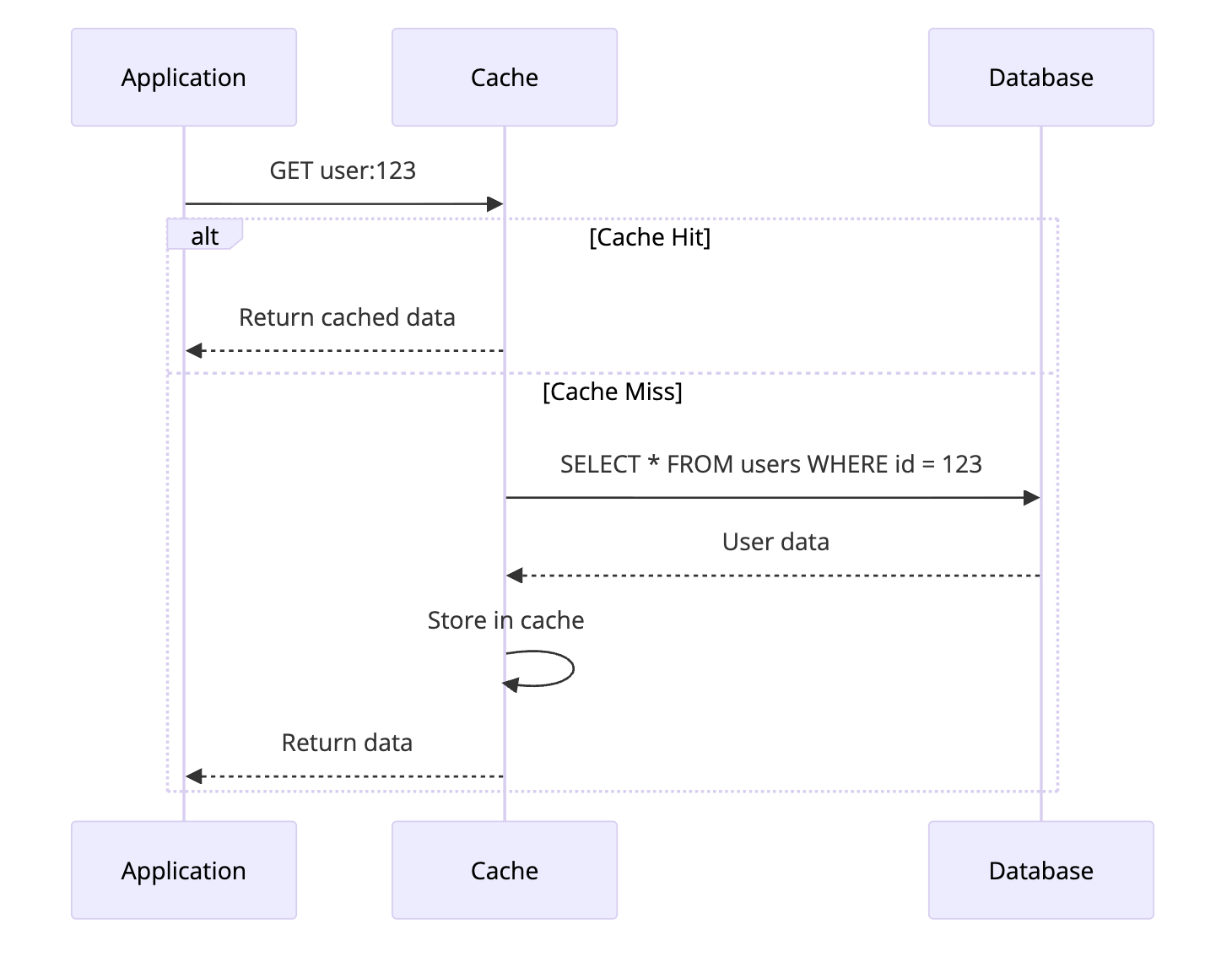

2. Read-Through Cache

Read-Through is like Cache-Aside, but the cache itself handles the database lookup on a miss. The application only talks to the cache.

How It Works

- Application requests data from cache

- If cache hit, return data

- If cache miss, cache fetches from database automatically

- Cache stores the data and returns it

The Key Difference from Cache-Aside

flowchart TB

subgraph CA["Cache-Aside"]

direction TB

A1[App] --> C1[Cache]

A1 --> D1[Database]

C1 -.->|Miss| A1

end

subgraph RT["Read-Through"]

direction TB

A2[App] --> C2[Cache]

C2 --> D2[Database]

end

CA ~~~ RT

In Cache-Aside, your application fetches from the database on a miss. In Read-Through, the cache handles that automatically.

Code Example

With Read-Through, your application code is simpler:

1

2

3

4

5

# Read-Through - Application code is simple

def get_user(user_id):

# Cache handles everything

# On miss, it fetches from DB automatically

return cache.get(f"user:{user_id}")

The cache is configured with a loader function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Cache configuration

cache = ReadThroughCache(

loader=lambda key: db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?",

key.split(":")[1]),

ttl=3600

)

When to Use Read-Through

You want simpler application code without cache management logic

Read-heavy workloads with predictable data access patterns

Using a cache that supports it (like AWS DAX for DynamoDB)

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Simpler application code | Less control over caching logic |

| Cache manages its own data | Cache must know how to load data |

| Consistent cache population | Not all caches support this pattern |

| Reduces code duplication | Harder to debug cache behavior |

Real World Usage

AWS DynamoDB Accelerator (DAX) is a Read-Through cache for DynamoDB. Your application queries DAX, and it automatically handles fetching from DynamoDB on cache misses.

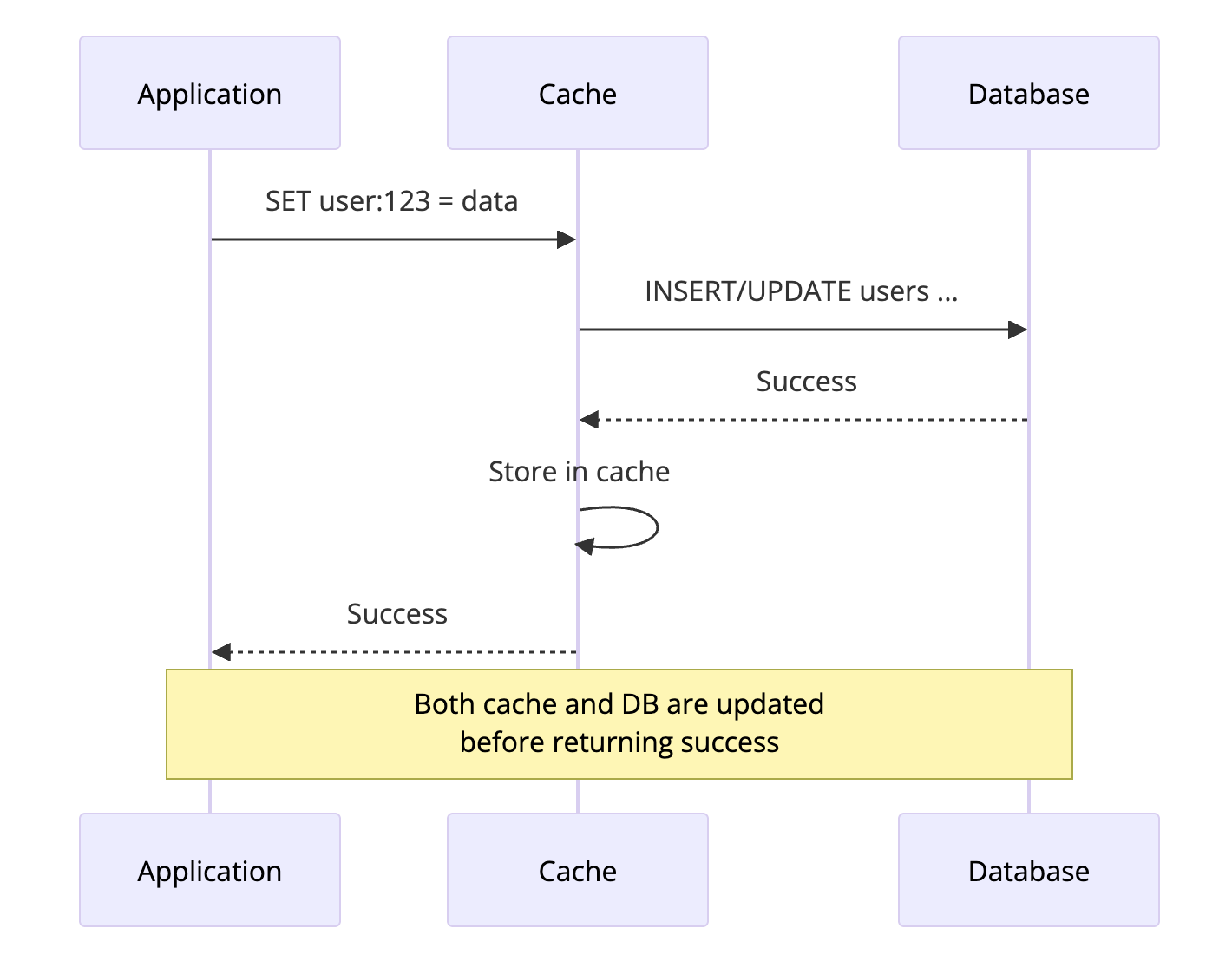

3. Write-Through Cache

Write-Through ensures the cache and database are always in sync. Every write goes to both the cache and database before returning success.

How It Works

- Application writes to cache

- Cache synchronously writes to database

- Only after both succeed, return success to application

Code Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

def update_user(user_id, data):

cache_key = f"user:{user_id}"

# Write-Through: cache handles both updates

# This is atomic - both succeed or both fail

cache.write_through(cache_key, data)

Behind the scenes, the cache implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class WriteThroughCache:

def write_through(self, key, value):

# Write to database first

self.db.write(key, value)

# Then update cache

self.cache.set(key, value)

# If either fails, the operation fails

When to Use Write-Through

Data consistency is critical (financial transactions, inventory counts)

You cannot afford stale reads after a write

Combined with Read-Through for a complete caching solution

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Cache and DB always in sync | Higher write latency |

| No stale data after writes | Writes are only as fast as DB |

| Simple consistency model | Not suitable for write-heavy workloads |

| Easy to reason about | Cache failures can block writes |

Real World Usage

Banking systems often use Write-Through for account balances. When you transfer money, both the cache and database are updated synchronously to ensure you never see inconsistent balances.

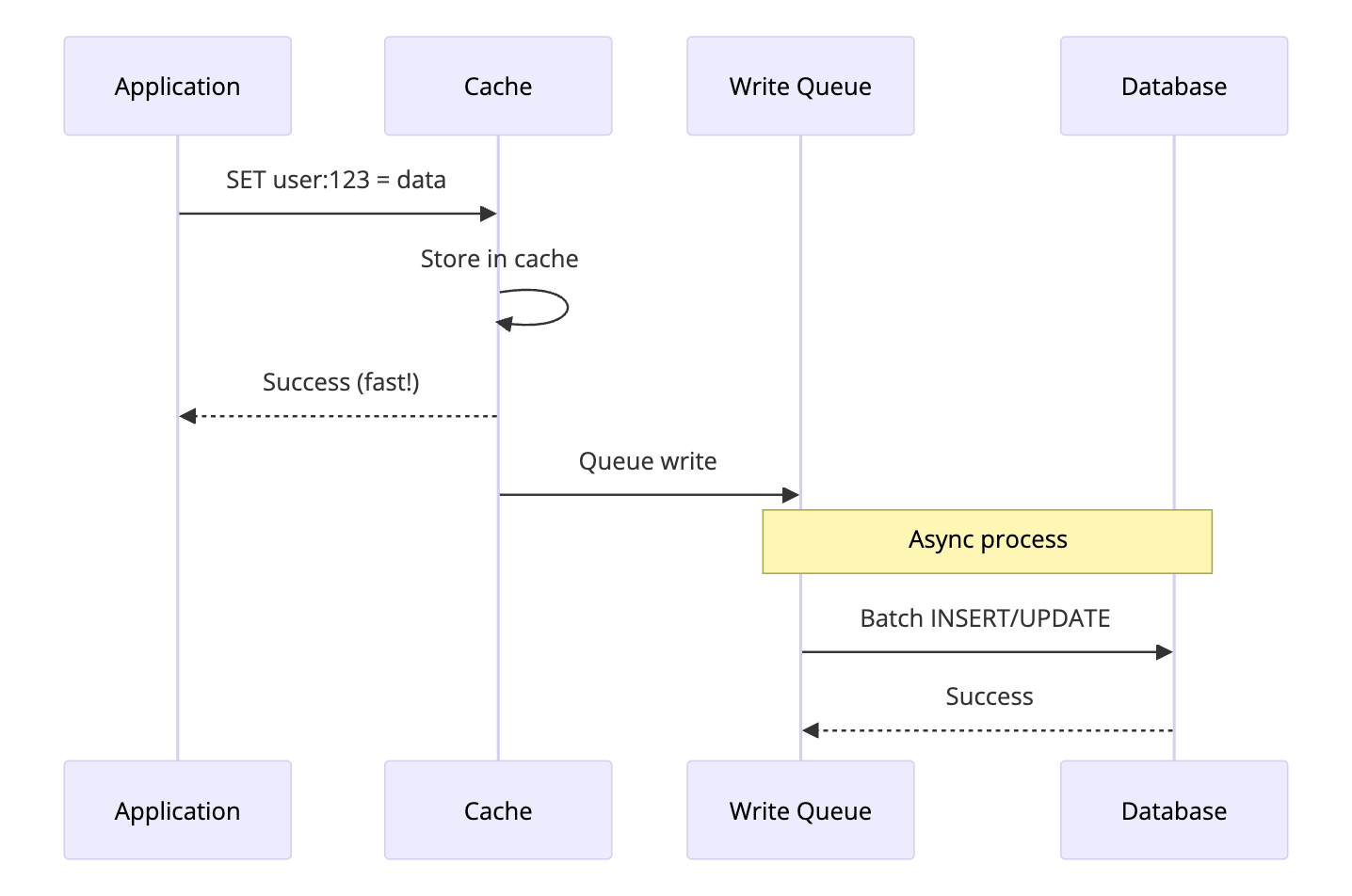

4. Write-Behind (Write-Back) Cache

Write-Behind prioritizes write performance over immediate consistency. Writes go to the cache first and are asynchronously persisted to the database later.

How It Works

- Application writes to cache

- Cache immediately returns success

- Cache queues the write

- Background process writes to database asynchronously

Code Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

class WriteBehindCache:

def __init__(self):

self.write_queue = Queue()

self.start_background_writer()

def set(self, key, value):

# Update cache immediately

self.cache.set(key, value)

# Queue for async database write

self.write_queue.put((key, value))

return True # Return immediately

def background_writer(self):

while True:

batch = []

# Collect writes for batching

while len(batch) < 100 and not self.write_queue.empty():

batch.append(self.write_queue.get())

if batch:

# Batch write to database

self.db.batch_write(batch)

time.sleep(0.1) # Write every 100ms

When to Use Write-Behind

Write-heavy workloads where write performance is critical

You can tolerate eventual consistency (data will sync, but not immediately)

Batching writes provides benefit (reduces database load)

Short bursts of high write volume (absorb spikes in cache)

The Risk: Data Loss

graph TD

subgraph "Normal Operation"

A1[Write to Cache] --> B1[Queue Write]

B1 --> C1[Async Write to DB]

C1 --> D1[Data Safe]

end

subgraph "Failure Scenario"

A2[Write to Cache] --> B2[Queue Write]

B2 --> C2[Cache Crashes]

C2 --> D2[Data Lost!]

style C2 fill:#ffcccc

style D2 fill:#ff9999

end

If the cache fails before syncing to the database, you lose data. This is the main risk of Write-Behind.

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Fastest write performance | Risk of data loss on cache failure |

| Reduces database load | Complex failure handling |

| Can batch multiple writes | Eventual consistency only |

| Absorbs traffic spikes | Harder to debug data issues |

Real World Usage

Netflix uses Write-Behind for view history. When you watch something, it immediately updates in cache. The database is updated asynchronously. If cache fails before sync, you might lose a few seconds of viewing history, which is acceptable.

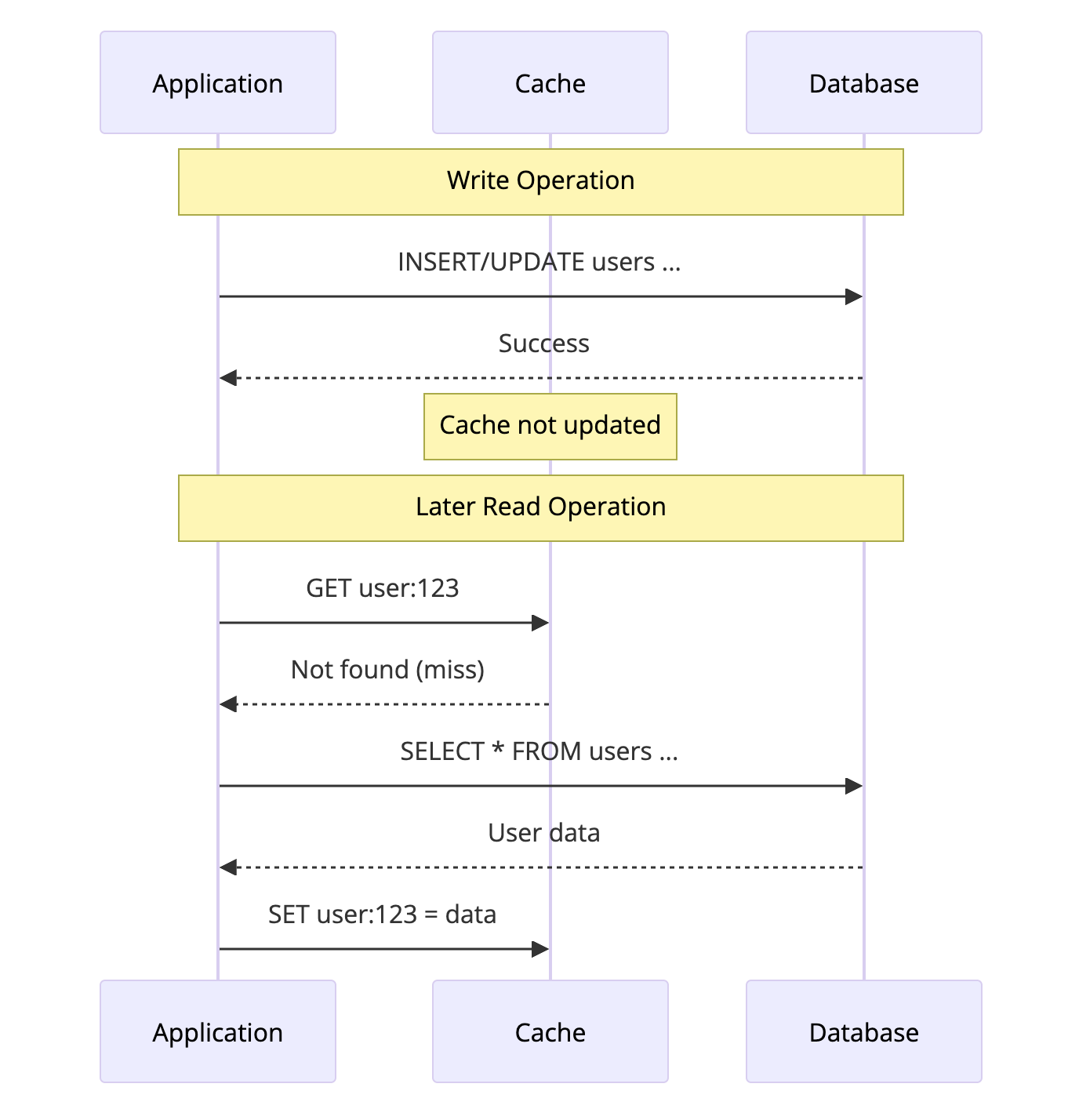

5. Write-Around Cache

Write-Around skips the cache entirely for writes. Data is written directly to the database, and the cache is only populated on reads.

How It Works

- Application writes directly to database (cache is bypassed)

- Cache is not updated

- On next read, data is loaded into cache

Code Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

def create_log_entry(log_data):

# Write directly to database, skip cache

db.execute("INSERT INTO logs ...", log_data)

# Cache is not updated

def get_user(user_id):

# Normal Cache-Aside for reads

cached = cache.get(f"user:{user_id}")

if cached:

return cached

user = db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?", user_id)

cache.set(f"user:{user_id}", user)

return user

When to Use Write-Around

Data is written once but rarely read (logs, audit trails)

You do not want writes to pollute the cache with data that may never be read

Bulk data imports where you are loading lots of data but only some will be accessed

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Cache only stores actually-read data | First read after write is slow |

| Prevents cache pollution | Cache and DB can be inconsistent |

| Good for write-once-read-maybe data | Not suitable for read-after-write scenarios |

| Simple to implement | Requires careful invalidation |

Real World Usage

Logging systems often use Write-Around. Log entries are written to the database, but only recent or searched logs are cached. This prevents the cache from filling up with old logs that nobody reads.

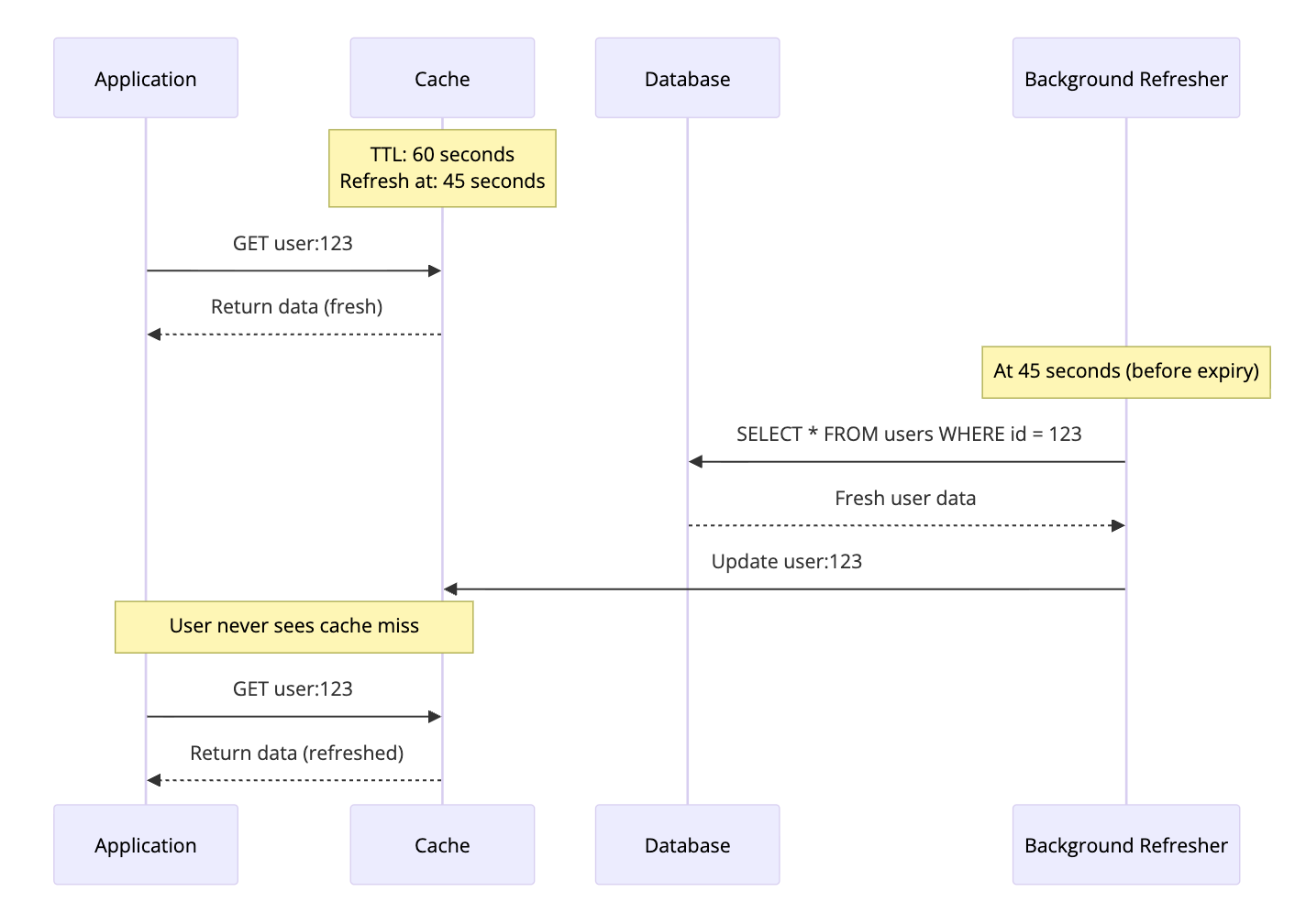

6. Refresh-Ahead Cache

Refresh-Ahead proactively refreshes cache entries before they expire. Instead of waiting for a cache miss, the cache predicts which data will be needed and refreshes it in the background.

How It Works

- Cache tracks access patterns

- Before expiration, cache refreshes frequently accessed data

- User requests always hit warm cache

Code Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

class RefreshAheadCache:

def __init__(self, ttl=60, refresh_threshold=0.75):

self.ttl = ttl

self.refresh_threshold = refresh_threshold # Refresh at 75% of TTL

def get(self, key):

entry = self.cache.get_with_metadata(key)

if not entry:

# Cache miss - load synchronously

return self.load_and_cache(key)

# Check if we should refresh

age = time.now() - entry.created_at

threshold = self.ttl * self.refresh_threshold

if age > threshold:

# Trigger background refresh

self.refresh_async(key)

return entry.value

def refresh_async(self, key):

# Non-blocking refresh

thread = Thread(target=self.load_and_cache, args=[key])

thread.start()

When to Use Refresh-Ahead

Predictable access patterns where you know what data will be accessed

Low latency is critical and you cannot afford cache misses

Session data or user preferences that are accessed frequently

Configuration data that should always be fresh

Tradeoffs

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Eliminates cache misses for hot data | Uses more resources (proactive fetches) |

| Consistent low latency | Complex to implement correctly |

| Keeps cache warm | May refresh data that is not needed |

| Good for predictable workloads | Prediction accuracy matters |

Real World Usage

CDNs like Cloudflare use Refresh-Ahead for popular content. They track which resources are frequently accessed and proactively refresh them before the cache expires, ensuring users always get fast responses.

Cache Eviction Policies

No matter which strategy you use, your cache has limited memory. When it is full, something has to go. Eviction policies decide what gets removed.

The Main Eviction Policies

| Policy | Full Name | What It Does | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRU | Least Recently Used | Evicts items not accessed recently | General purpose, most common |

| LFU | Least Frequently Used | Evicts items with lowest access count | Stable access patterns |

| FIFO | First In First Out | Evicts oldest items regardless of access | Simple use cases |

| TTL | Time To Live | Evicts items after fixed time period | Time-sensitive data |

| Random | Random Eviction | Evicts random items | Testing, fallback |

LRU (Least Recently Used)

Removes items that have not been accessed for the longest time.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# LRU Cache behavior

cache.set("A", 1) # Cache: [A]

cache.set("B", 2) # Cache: [A, B]

cache.set("C", 3) # Cache: [A, B, C]

cache.get("A") # Access A, moves to end: [B, C, A]

cache.set("D", 4) # Cache full, evict B (least recent): [C, A, D]

Best for: General purpose caching, most common choice

LFU (Least Frequently Used)

Removes items with the lowest access count.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# LFU Cache behavior

cache.set("A", 1) # A: count=1

cache.get("A") # A: count=2

cache.get("A") # A: count=3

cache.set("B", 2) # B: count=1

# When evicting, B goes first (lower count)

Best for: Data with stable access patterns, CDN caching

TTL (Time To Live)

Items expire after a fixed time, regardless of access.

1

2

3

cache.set("session", data, ttl=3600) # Expires in 1 hour

# After 1 hour, item is automatically removed

Best for: Session data, temporary tokens, data that must be fresh

Comparison Table

| Policy | Best For | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRU | General use | Simple, effective | Scan resistance issues |

| LFU | Stable patterns | Keeps truly hot items | Slow to adapt to changes |

| FIFO | Simple needs | Very simple | Ignores access patterns |

| TTL | Time-sensitive data | Guarantees freshness | May evict hot items |

| Random | Testing/fallback | No overhead | Unpredictable |

Cache Invalidation: The Hard Part

There is a famous quote in computer science:

“There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.” — Phil Karlton

Cache invalidation is deciding when and how to remove stale data from the cache.

Invalidation Strategies

| Strategy | How It Works | Tradeoff |

|---|---|---|

| TTL-based | Expire after fixed time | Simple but allows stale window |

| Event-based | Invalidate on data write | Immediate but requires tracking |

| Version-based | Include version in cache key | No stale data but higher cache miss |

| Manual Purge | Explicit invalidation call | Full control but manual effort |

TTL-based Invalidation

Set an expiration time. Accept that data may be stale within that window.

1

2

# Data may be up to 5 minutes stale

cache.set("user:123", user_data, ttl=300)

When to use: When you can tolerate some staleness

Event-based Invalidation

Invalidate cache when the underlying data changes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def update_user(user_id, data):

db.update("users", user_id, data)

cache.delete(f"user:{user_id}") # Invalidate immediately

def update_product(product_id, data):

db.update("products", product_id, data)

# Invalidate all related caches

cache.delete(f"product:{product_id}")

cache.delete(f"category:{data['category_id']}")

cache.delete("featured_products")

When to use: When consistency is important

Version-based Invalidation

Include a version in the cache key. When data changes, increment version.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

def get_user(user_id):

version = db.get_version("user", user_id)

cache_key = f"user:{user_id}:v{version}"

cached = cache.get(cache_key)

if cached:

return cached

user = db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?", user_id)

cache.set(cache_key, user)

return user

def update_user(user_id, data):

db.update("users", user_id, data)

db.increment_version("user", user_id)

# Old cache key becomes irrelevant

When to use: When you cannot easily track all cache dependencies

Common Caching Mistakes

Mistake 1: Caching Everything

Not all data benefits from caching. Cache data that is:

- Read frequently

- Expensive to compute or fetch

- Relatively stable

1

2

3

4

5

# Bad: Caching rarely accessed data wastes memory

cache.set(f"user:{user_id}:login_history", history) # Who reads this?

# Good: Cache frequently accessed, stable data

cache.set(f"user:{user_id}:profile", profile)

Mistake 2: No TTL

Without TTL, stale data lives forever.

1

2

3

4

5

# Bad: No expiration

cache.set("exchange_rates", rates)

# Good: Appropriate TTL

cache.set("exchange_rates", rates, ttl=300) # 5 minutes

Mistake 3: Cache Stampede

When a popular cache entry expires, hundreds of requests hit the database simultaneously.

sequenceDiagram

participant R1 as Request 1

participant R2 as Request 2

participant R3 as Request 3

participant Cache as Cache

participant DB as Database

Note over Cache: Popular item expires

R1->>Cache: GET popular_item

Cache-->>R1: Miss

R2->>Cache: GET popular_item

Cache-->>R2: Miss

R3->>Cache: GET popular_item

Cache-->>R3: Miss

R1->>DB: Query

R2->>DB: Query

R3->>DB: Query

Note over DB: Database overloaded!

Solution: Use locking or probabilistic early expiration. This is known as the thundering herd problem and it can take down entire systems during peak traffic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def get_with_lock(key):

data = cache.get(key)

if data:

return data

# Try to acquire lock

if cache.set(f"lock:{key}", 1, nx=True, ttl=5):

# We have the lock, fetch data

data = db.query(...)

cache.set(key, data)

cache.delete(f"lock:{key}")

return data

else:

# Someone else is fetching, wait and retry

time.sleep(0.1)

return get_with_lock(key)

Mistake 4: Not Handling Cache Failures

Cache is not your database. It can fail.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# Bad: Crash if cache fails

def get_user(user_id):

return cache.get(f"user:{user_id}") # What if cache is down?

# Good: Fall back to database

def get_user(user_id):

try:

cached = cache.get(f"user:{user_id}")

if cached:

return cached

except CacheError:

pass # Cache is down, continue to database

return db.query("SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?", user_id)

Choosing the Right Strategy

Here is a quick reference:

| Scenario | Recommended Strategy |

|---|---|

| General purpose caching | Cache-Aside |

| Read-heavy, simple code | Read-Through |

| Data consistency critical | Write-Through |

| High write throughput | Write-Behind |

| Write-once, read-maybe | Write-Around |

| Predictable access, low latency | Refresh-Ahead |

Combining Strategies

Most production systems combine multiple strategies:

Read-Through + Write-Through: Full consistency, simple application code

Cache-Aside + Write-Around: Control over reads, skip cache for bulk writes

Read-Through + Write-Behind: Simple reads, high write performance

Real World Implementations

Redis

Redis supports multiple patterns through its command set:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

import redis

r = redis.Redis()

# Cache-Aside

def get_user(user_id):

key = f"user:{user_id}"

user = r.get(key)

if user:

return json.loads(user)

user = db.query(user_id)

r.setex(key, 3600, json.dumps(user)) # TTL of 1 hour

return user

# Write-Through (application managed)

def update_user(user_id, data):

db.update(user_id, data)

r.setex(f"user:{user_id}", 3600, json.dumps(data))

Memcached

Memcached is optimized for simple key-value caching:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

import memcache

mc = memcache.Client(['127.0.0.1:11211'])

# Simple Cache-Aside

def get_user(user_id):

key = f"user:{user_id}"

user = mc.get(key)

if user:

return user

user = db.query(user_id)

mc.set(key, user, time=3600)

return user

CDN Caching

CDNs like Cloudflare implement caching at the edge:

1

2

3

4

5

# Cache-Control header for CDN caching

Cache-Control: public, max-age=3600, s-maxage=86400

# max-age: Browser cache for 1 hour

# s-maxage: CDN cache for 24 hours

Key Takeaways

-

Cache-Aside is the default choice. Start here unless you have specific requirements.

-

Write-Through for consistency. When you cannot afford stale reads after writes.

-

Write-Behind for performance. When write speed matters more than immediate consistency.

-

Always set TTL. Stale data is often worse than no cache.

-

Handle cache failures gracefully. The cache is not your source of truth.

-

Cache invalidation is hard. Plan your invalidation strategy before implementing caching.

-

Measure before optimizing. Cache what actually needs caching based on real access patterns.

Further Reading:

- How Meta Achieves Cache Consistency - Deep dive into Facebook’s caching architecture

- How Consistent Hashing Works - How distributed caches distribute keys across servers

- Redis Documentation - Official Redis caching patterns

- AWS ElastiCache Best Practices - Production caching guidance

- Memcached Wiki - Memcached patterns and usage

Building a high-traffic system? Check out How OpenAI Scales PostgreSQL to 800M Users for caching + database scaling patterns, the System Design Cheat Sheet for a complete reference, and How Stripe Prevents Double Payments for idempotency patterns.