A modular monolith is a single deployable app with well-defined modules that communicate through explicit interfaces, not by reaching into each other’s internals. Combines monolith simplicity (single deploy, no network calls) with microservice organization (clear boundaries, team autonomy). Shopify and GitHub use this. Easy to extract modules to services later.

Microservices aren’t always the answer. For most teams, they bring network latency, distributed debugging nightmares, and operational overhead that outweighs the benefits. But a tangled monolith where everything depends on everything isn’t great either.

There’s a middle ground: the modular monolith. Clear boundaries and team autonomy without the distributed systems tax. It’s how Shopify handles billions in Black Friday sales with a single deployable application—and why companies like Basecamp and GitHub chose this path too.

What is a Modular Monolith?

A modular monolith is a single deployable application that’s internally divided into well-defined modules. Each module owns its domain, has clear boundaries, and communicates with other modules through explicit interfaces.

Think of it like an apartment building:

- Traditional monolith: One giant open floor plan. Everyone shares everything. Chaos.

- Microservices: Separate houses scattered across the city. Complete isolation but expensive travel.

- Modular monolith: Apartments in a building. Private spaces with shared infrastructure.

Traditional Monolith — Everything in one place, no boundaries:

flowchart LR

subgraph Traditional["Traditional Monolith"]

UI[User Interface] --> BL[Business Logic]

BL --> DAL[Data Access]

DAL --> DB[(Database)]

UI --> Utils[Shared Utilities]

BL --> Utils

DAL --> Utils

UI -.->|"Direct Access"| DAL

BL -.->|"Reaches into everything"| DB

end

style Traditional fill:#fff8e1,stroke:#f57f17,stroke-width:2px

style DB fill:#ffcdd2,stroke:#c62828

style Utils fill:#ffcdd2,stroke:#c62828

Modular Monolith — Clear boundaries, shared infrastructure:

flowchart TB

subgraph Modular["Modular Monolith - Single Deployment"]

subgraph Orders["fa:fa-box Orders Module"]

O_API[Public API]

O_Logic[Order Logic]

O_Data[Order Data]

O_API --> O_Logic --> O_Data

end

subgraph Payments["fa:fa-credit-card Payments Module"]

P_API[Public API]

P_Logic[Payment Logic]

P_Data[Payment Data]

P_API --> P_Logic --> P_Data

end

subgraph Inventory["fa:fa-warehouse Inventory Module"]

I_API[Public API]

I_Logic[Inventory Logic]

I_Data[Inventory Data]

I_API --> I_Logic --> I_Data

end

SharedDB[(Shared Database)]

O_Data --> SharedDB

P_Data --> SharedDB

I_Data --> SharedDB

O_API -.->|"Through API only"| P_API

O_API -.->|"Through API only"| I_API

end

style Modular fill:#e8f5e9,stroke:#2e7d32,stroke-width:2px

style Orders fill:#c8e6c9,stroke:#388e3c

style Payments fill:#c8e6c9,stroke:#388e3c

style Inventory fill:#c8e6c9,stroke:#388e3c

style SharedDB fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px

Microservices — Complete isolation, network overhead:

flowchart TB

subgraph Microservices["Microservices - Separate Deployments"]

subgraph OS["Order Service"]

OS_API[API]

OS_Logic[Logic]

end

OS_DB[(Order DB)]

subgraph PS["Payment Service"]

PS_API[API]

PS_Logic[Logic]

end

PS_DB[(Payment DB)]

subgraph IS["Inventory Service"]

IS_API[API]

IS_Logic[Logic]

end

IS_DB[(Inventory DB)]

OS_Logic --> OS_DB

PS_Logic --> PS_DB

IS_Logic --> IS_DB

OS_API <-.->|"Network Call"| PS_API

OS_API <-.->|"Network Call"| IS_API

PS_API <-.->|"Network Call"| IS_API

end

style Microservices fill:#e3f2fd,stroke:#1565c0,stroke-width:2px

style OS fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#1976d2

style PS fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#1976d2

style IS fill:#bbdefb,stroke:#1976d2

style OS_DB fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#7b1fa2

style PS_DB fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#7b1fa2

style IS_DB fill:#e1bee7,stroke:#7b1fa2

The key difference from a traditional monolith: enforced boundaries. Code in the Orders module can’t just reach into Payments and grab whatever data it wants. It has to go through a defined interface.

Why Not Just Use Microservices?

Microservices solve real problems. When you have hundreds of developers, you need autonomous teams. When you need to scale specific components independently, microservices make sense.

But they come with a tax:

| Microservices Tax | Cost |

|---|---|

| Network latency | Every call adds 1-10ms |

| Partial failures | What happens when one service is down? |

| Data consistency | No more ACID transactions across services |

| Operational complexity | Kubernetes, service mesh, distributed tracing |

| Developer experience | Running 10 services locally is painful |

| Debugging | Good luck tracing a request across 8 services |

For a team of 5-50 developers, this tax often outweighs the benefits.

The distributed monolith trap: Many teams end up with tightly coupled services that have to be deployed together. They have all the complexity of microservices with none of the independence. This is worse than a well-structured monolith.

flowchart LR

subgraph "Distributed Monolith - Worst of Both Worlds"

A[Service A] -->|Sync Call| B[Service B]

B -->|Sync Call| C[Service C]

C -->|Sync Call| D[Service D]

D -->|Sync Call| A

end

style A fill:#ffcdd2

style B fill:#ffcdd2

style C fill:#ffcdd2

style D fill:#ffcdd2

The Modular Monolith Sweet Spot

A modular monolith gives you:

What you keep from monoliths:

- Single deployment

- Simple local development

- ACID transactions when you need them

- No network overhead between modules

- Easy debugging with standard tools

What you gain from microservices thinking:

- Clear module boundaries

- Team autonomy within modules

- Prepared for future extraction

- Independent testing per module

- Domain-driven organization

Let me show you what this looks like in practice.

Anatomy of a Modular Monolith

Module Structure

Each module is a mini-application with its own layers:

graph TB

subgraph "Order Module"

direction TB

API[Public API / Facade]

App[Application Services]

Domain[Domain Logic]

Infra[Infrastructure]

Data[(Module Data)]

API --> App

App --> Domain

Domain --> Infra

Infra --> Data

end

External[Other Modules] -->|Only through API| API

style API fill:#c8e6c9

style External fill:#e3f2fd

The rules:

- Public API: The only way other modules can interact with this module

- Application Services: Orchestrate use cases

- Domain Logic: Business rules, pure code, no dependencies

- Infrastructure: Database access, external services

- Module Data: Tables owned exclusively by this module

Folder Structure

Here’s what a modular monolith looks like in code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

src/

├── modules/

│ ├── orders/

│ │ ├── api/

│ │ │ └── OrderFacade.java # Public interface

│ │ ├── application/

│ │ │ └── OrderService.java

│ │ ├── domain/

│ │ │ ├── Order.java

│ │ │ └── OrderRepository.java # Interface

│ │ └── infrastructure/

│ │ └── JpaOrderRepository.java

│ │

│ ├── payments/

│ │ ├── api/

│ │ │ └── PaymentFacade.java

│ │ ├── application/

│ │ ├── domain/

│ │ └── infrastructure/

│ │

│ └── inventory/

│ ├── api/

│ ├── application/

│ ├── domain/

│ └── infrastructure/

│

├── shared/ # Shared kernel (keep it small)

│ ├── Money.java

│ └── EventPublisher.java

│

└── Application.java

Each module lives in its own package. The api folder contains the only classes that other modules can access.

Enforcing Boundaries

The hardest part of a modular monolith is keeping modules separate. Without enforcement, developers will take shortcuts, and you’ll end up with a mess.

Option 1: Package-level access (Java)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// In orders module - package-private by default

class Order {

// Only accessible within orders module

}

// Public facade - the only entry point

public class OrderFacade {

public OrderDto getOrder(Long id) {

// ...

}

}

Option 2: Architecture tests with ArchUnit

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@AnalyzeClasses(packages = "com.myapp")

public class ModuleBoundaryTests {

@ArchTest

static final ArchRule orders_should_not_access_payment_internals =

noClasses()

.that().resideInAPackage("..orders..")

.should().accessClassesThat()

.resideInAPackage("..payments.domain..")

.orShould().accessClassesThat()

.resideInAPackage("..payments.infrastructure..");

}

This test fails the build if someone violates module boundaries.

Option 3: Separate build modules

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// build.gradle

project(':orders') {

dependencies {

implementation project(':shared')

// Cannot depend on other modules directly

}

}

project(':payments') {

dependencies {

implementation project(':shared')

}

}

Each module is a separate Gradle/Maven module. The compiler enforces boundaries.

Module Communication Patterns

Modules need to talk to each other. Here’s how to do it right.

Pattern 1: Synchronous Calls Through Facades

The simplest approach. Module A calls Module B’s public API.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

// In OrderService

public class OrderService {

private final InventoryFacade inventoryFacade;

private final PaymentFacade paymentFacade;

public Order createOrder(CreateOrderRequest request) {

// Check inventory

boolean available = inventoryFacade.checkAvailability(

request.getProductId(),

request.getQuantity()

);

if (!available) {

throw new InsufficientInventoryException();

}

// Create order

Order order = new Order(request);

orderRepository.save(order);

// Reserve inventory

inventoryFacade.reserve(order.getId(), request.getProductId());

return order;

}

}

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant OrderFacade

participant OrderService

participant InventoryFacade

participant PaymentFacade

Client->>OrderFacade: createOrder()

OrderFacade->>OrderService: createOrder()

OrderService->>InventoryFacade: checkAvailability()

InventoryFacade-->>OrderService: true

OrderService->>OrderService: save order

OrderService->>InventoryFacade: reserve()

OrderService-->>OrderFacade: Order

OrderFacade-->>Client: OrderDto

Pros:

- Simple to understand

- Easy to debug

- Transaction support

Cons:

- Creates coupling between modules

- Synchronous means waiting

Pattern 2: Domain Events

Modules communicate through events. When something happens in Module A, it publishes an event. Module B subscribes and reacts.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

// In Orders module

public class Order {

public void complete() {

this.status = Status.COMPLETED;

// Publish event

DomainEvents.publish(new OrderCompletedEvent(this.id, this.items));

}

}

// In Inventory module

@EventListener

public class InventoryEventHandler {

public void handle(OrderCompletedEvent event) {

// Reduce inventory for each item

event.getItems().forEach(item ->

inventoryService.reduce(item.getProductId(), item.getQuantity())

);

}

}

sequenceDiagram

participant Order

participant EventBus

participant Inventory

participant Notification

Order->>Order: complete()

Order->>EventBus: publish(OrderCompleted)

par Parallel handlers

EventBus->>Inventory: handle(OrderCompleted)

Inventory->>Inventory: reduce stock

and

EventBus->>Notification: handle(OrderCompleted)

Notification->>Notification: send email

end

Pros:

- Loose coupling

- Easy to add new subscribers

- Modules don’t need to know about each other

Cons:

- Harder to debug (who’s handling this event?)

- Eventually consistent

- Event ordering can be tricky

Pattern 3: Shared Data Through Views

Sometimes modules need to read (but not write) each other’s data. Instead of direct database access, expose read-only views.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// Orders module exposes a read model

public interface OrderReadModel {

List<OrderSummary> getOrdersForCustomer(Long customerId);

OrderSummary getOrderSummary(Long orderId);

}

// Payments module uses it

public class PaymentService {

private final OrderReadModel orderReadModel;

public void processRefund(Long orderId) {

OrderSummary order = orderReadModel.getOrderSummary(orderId);

// Process refund based on order amount

}

}

This is similar to how CQRS separates reads and writes. The read model is optimized for queries and doesn’t expose internal domain logic.

Database Strategy: To Share or Not to Share

One of the biggest decisions: how do modules access data?

Option 1: Shared Database, Separate Schemas

All modules use the same database but own different tables.

graph TB

subgraph "Application"

Orders[Orders Module]

Payments[Payments Module]

Inventory[Inventory Module]

end

subgraph "Database"

subgraph "orders schema"

OT1[orders]

OT2[order_items]

end

subgraph "payments schema"

PT1[payments]

PT2[refunds]

end

subgraph "inventory schema"

IT1[products]

IT2[stock_levels]

end

end

Orders --> OT1

Orders --> OT2

Payments --> PT1

Payments --> PT2

Inventory --> IT1

Inventory --> IT2

style OT1 fill:#e3f2fd

style OT2 fill:#e3f2fd

style PT1 fill:#c8e6c9

style PT2 fill:#c8e6c9

style IT1 fill:#fff3e0

style IT2 fill:#fff3e0

Rules:

- Module X can only query tables in schema X

- No foreign keys across schemas

- If you need data from another module, call its API

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// WRONG: Direct cross-schema query

SELECT o.*, p.*

FROM orders.orders o

JOIN payments.payments p ON o.id = p.order_id

// RIGHT: Call through facade

Order order = orderFacade.getOrder(orderId);

Payment payment = paymentFacade.getPaymentForOrder(orderId);

Pros:

- Simple transactions within a module

- Easy to extract modules later (just move the schema)

- Works with existing ORMs

Cons:

- Requires discipline to not cross schemas

- Shared database is a single point of failure

Option 2: Logical Separation in Same Schema

For smaller applications, you might use the same schema but prefix tables.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

-- Orders module owns these

orders_orders

orders_order_items

orders_order_history

-- Payments module owns these

payments_payments

payments_refunds

-- Inventory module owns these

inventory_products

inventory_stock_levels

Same rules apply: never query tables you don’t own.

Option 3: Separate Databases Per Module

Each module has its own database. This is closest to microservices but still a single deployment.

graph TB

subgraph "Application - Single Deployment"

Orders[Orders Module]

Payments[Payments Module]

Inventory[Inventory Module]

end

Orders --> DB1[(Orders DB)]

Payments --> DB2[(Payments DB)]

Inventory --> DB3[(Inventory DB)]

style DB1 fill:#e3f2fd

style DB2 fill:#c8e6c9

style DB3 fill:#fff3e0

Pros:

- Complete data isolation

- Can use different database types per module

- Easiest path to microservices

Cons:

- No cross-module transactions

- More complex local development

- Higher operational overhead

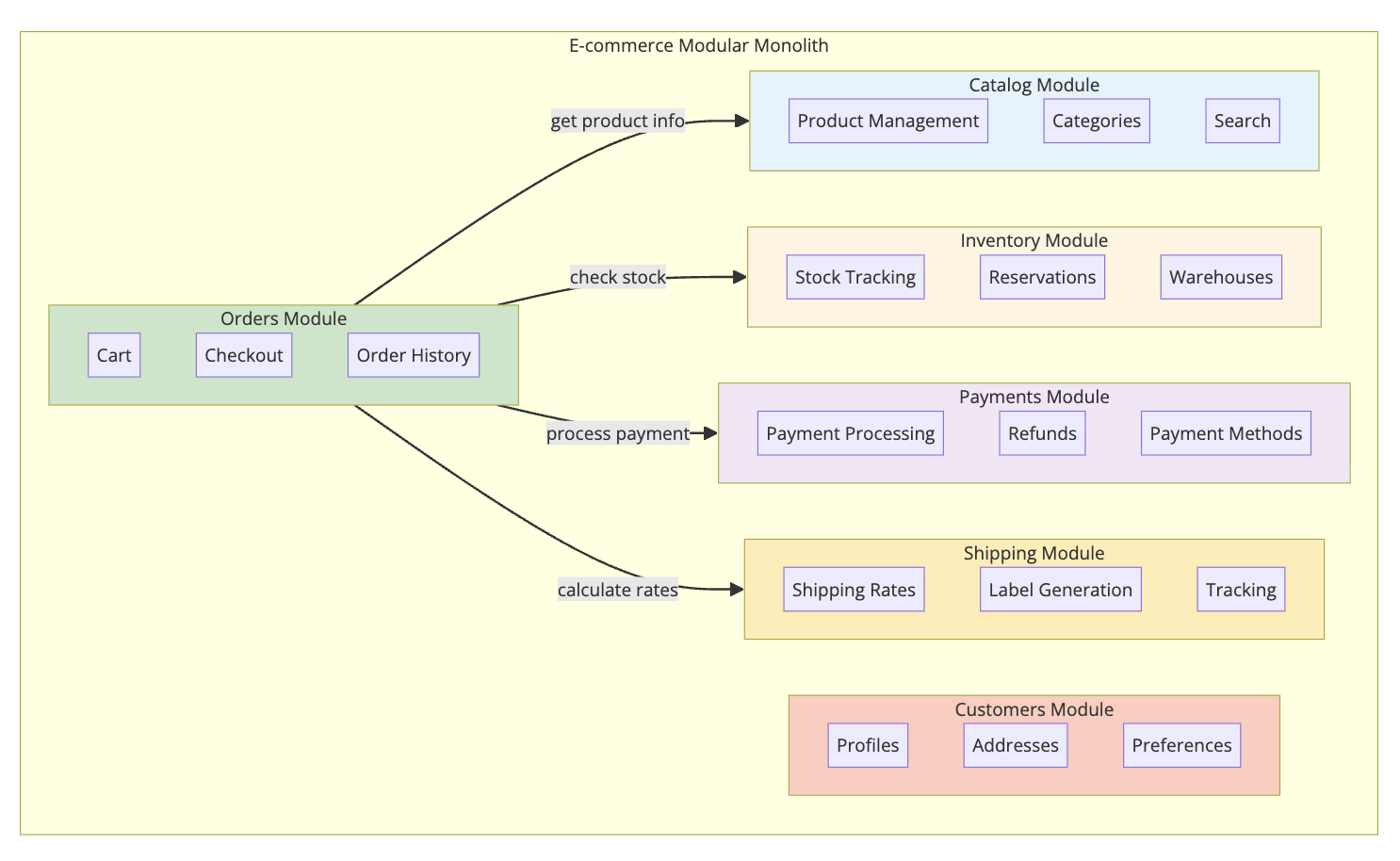

Real World Example: E-commerce Platform

Let’s design an e-commerce system as a modular monolith.

Identifying Modules

Start by identifying bounded contexts (DDD term for cohesive business areas):

Module Interactions

Here’s how checkout works:

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Orders

participant Catalog

participant Inventory

participant Payments

participant Shipping

Client->>Orders: checkout(cart)

Orders->>Catalog: getProducts(productIds)

Catalog-->>Orders: products with prices

Orders->>Inventory: reserveItems(items)

Inventory-->>Orders: reservation confirmed

Orders->>Shipping: calculateRates(address, items)

Shipping-->>Orders: shipping options

Orders->>Orders: create order

Orders->>Payments: processPayment(order, paymentMethod)

Payments-->>Orders: payment confirmed

Orders->>Inventory: confirmReservation(orderId)

Orders-->>Client: order confirmation

Note over Orders: Publish OrderCreated event

Orders->>Shipping: Event: OrderCreated

Shipping->>Shipping: Generate label

Handling Failures

What if payment fails after inventory is reserved?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

public class CheckoutService {

@Transactional

public Order checkout(Cart cart, PaymentMethod paymentMethod) {

// 1. Validate and reserve inventory

Reservation reservation = inventoryFacade.reserve(cart.getItems());

try {

// 2. Create order

Order order = createOrder(cart, reservation);

// 3. Process payment

PaymentResult result = paymentFacade.processPayment(

order.getId(),

order.getTotal(),

paymentMethod

);

if (!result.isSuccessful()) {

throw new PaymentFailedException(result.getError());

}

// 4. Confirm reservation

inventoryFacade.confirmReservation(reservation.getId());

return order;

} catch (Exception e) {

// Release reservation on any failure

inventoryFacade.releaseReservation(reservation.getId());

throw e;

}

}

}

Because everything runs in the same process, you can use database transactions for consistency. Try doing this cleanly with microservices.

Shopify: The Modular Monolith Success Story

Shopify runs one of the largest e-commerce platforms on the planet. During Black Friday 2023, they processed over $9 billion in sales. Their architecture? A modular monolith built with Ruby on Rails.

As I covered in How Shopify Powers 5 Million Stores, they chose this architecture deliberately.

Why Shopify stayed with a modular monolith:

- Team productivity: Developers can work on features without understanding 50 different services

- Deployment simplicity: One artifact to deploy, test, and rollback

- Performance: No network calls between modules means faster response times

- Debugging: Stack traces make sense. No distributed tracing needed.

How they enforce modularity:

- Packwerk: A tool they built to enforce module boundaries in Ruby

- Rails Engines: Each module is a mini-Rails application

- Componentization: Clear public APIs for each module

Their monolith is so large that it has over 2.8 million lines of Ruby code. Yet they deploy it multiple times per day with hundreds of developers.

When to Choose Modular Monolith

Here’s a decision framework:

Choose Modular Monolith When:

| Situation | Why Modular Monolith |

|---|---|

| Team size < 50 developers | Single codebase is manageable |

| Domain isn’t well understood | Easy to refactor boundaries |

| Strong consistency needed | Database transactions work |

| Fast iteration required | No distributed system overhead |

| Limited DevOps capacity | One thing to deploy and monitor |

| Starting a new project | Get boundaries right first |

Choose Microservices When:

| Situation | Why Microservices |

|---|---|

| Team size > 100 developers | Need autonomous teams |

| Different scaling requirements | Scale components independently |

| Different tech stacks needed | Each service can use best tool |

| Strong team boundaries | Ownership is crystal clear |

| High availability requirements | Fault isolation between services |

Key Takeaways

1. Modular monolith is not a compromise. It’s a legitimate architecture choice used by companies processing billions in transactions.

2. Start simple, evolve when needed. You can always extract modules into services later. You can’t easily merge distributed services back together.

3. Boundaries are everything. A modular monolith without enforced boundaries is just a monolith with folders.

4. Single deployment, multiple modules. You get the organizational benefits of separation without the operational cost of distribution.

5. Transaction support is underrated. When you need strong consistency, a single database makes life much easier.

6. The hard part is discipline. The architecture doesn’t prevent you from crossing boundaries. Tests and tooling do.

7. It’s a stepping stone, not a dead end. Well-defined modules can be extracted to services when you actually need it.

Most teams don’t need microservices. They need good architecture. A modular monolith gives you that without the distributed systems tax.

The next time someone suggests microservices for a new project, ask: “What problem are we solving that a modular monolith can’t?”

You might be surprised by the silence.

Building a system that needs to scale? Check out How Shopify Powers 5 Million Stores for a deep dive into their modular monolith, and How Kafka Works when you need event-driven communication between modules.

References: Martin Fowler on Monolith First, Sam Newman on Distributed Monoliths, Shopify Engineering Blog, Kamil Grzybek - Modular Monolith Primer