Message queues decouple services, absorb traffic spikes, and enable async processing. Kafka: high-throughput streaming with replay. RabbitMQ: complex routing and request-reply. SQS: simple AWS-native. Dead letter queues store failed messages for debugging. Pub/sub broadcasts to all subscribers; point-to-point delivers to one consumer.

Your checkout page just went viral on Twitter. Orders are flooding in. The payment service is getting hammered. Database connections are maxing out. Your monitoring dashboard is screaming red.

This is the moment when most systems break. But well designed systems? They stay calm. They use queues.

Message queues are one of those patterns that separate systems that scale from systems that crash. Yet many developers treat queues as an afterthought. They bolt them on when things start breaking.

Let’s fix that. By the end of this post, you’ll understand exactly when to use queues, which queue technology to pick, and how companies like Uber, Slack, and Stripe use them to handle millions of requests.

The Problem: Tight Coupling Breaks Systems

Picture a simple e-commerce checkout flow:

sequenceDiagram

participant User

participant API as Checkout API

participant Payment as Payment Service

participant Inventory as Inventory Service

participant Email as Email Service

participant Analytics as Analytics

User->>API: Place Order

API->>Payment: Charge Card

Payment->>API: Success

API->>Inventory: Reserve Items

Inventory->>API: Reserved

API->>Email: Send Confirmation

Email->>API: Sent

API->>Analytics: Log Purchase

Analytics->>API: Logged

API->>User: Order Complete (2.3s total)

This works fine with 10 users. But what happens at scale?

Problem 1: Latency adds up. Each service call takes 200-500ms. Chain four services together and your checkout takes 2+ seconds. Users abandon carts.

Problem 2: One slow service blocks everything. If the email service takes 3 seconds because of a spam filter check, your entire checkout waits 3 seconds.

Problem 3: One failing service kills the whole flow. Analytics service is down? Checkout fails. Even though analytics isn’t critical to completing an order.

Problem 4: No way to handle traffic spikes. Black Friday hits, orders spike 10x. All your downstream services must handle 10x load simultaneously. If any one of them can’t, the whole system falls over.

This is what we call tight coupling. Every component depends on every other component being fast and available.

The Solution: Decouple with Queues

A queue sits between services. Instead of calling services directly, you drop a message on the queue. The service picks it up when it’s ready.

sequenceDiagram

participant User

participant API as Checkout API

participant Payment as Payment Service

participant Queue as Message Queue

participant Inventory as Inventory Worker

participant Email as Email Worker

participant Analytics as Analytics Worker

User->>API: Place Order

API->>Payment: Charge Card

Payment->>API: Success

API->>Queue: Publish "OrderCreated"

API->>User: Order Complete (400ms)

Note over Queue,Analytics: Async Processing

Queue->>Inventory: Process reservation

Queue->>Email: Send confirmation

Queue->>Analytics: Log purchase

Now your checkout is fast. The user gets a response in 400ms instead of 2.3 seconds. Everything else happens in the background.

Benefit 1: Faster responses. Only critical operations block the user. Everything else is async.

Benefit 2: Fault isolation. Email service down? Messages pile up in the queue. When it recovers, it processes the backlog. Users never notice.

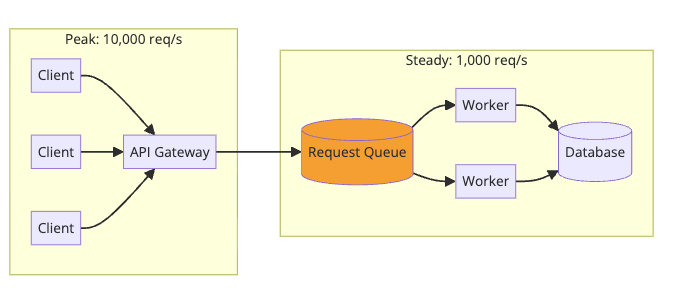

Benefit 3: Traffic smoothing. A sudden spike of 10,000 orders doesn’t hit your services all at once. The queue absorbs the burst, and workers process at their own pace. This is one of the most effective ways to prevent the thundering herd problem in write heavy systems.

Benefit 4: Independent scaling. Your email worker is slow? Add more email workers. No need to scale the entire system.

Core Concepts Every Developer Should Know

Producers and Consumers

The two actors in any queue system:

- Producer: Creates messages and puts them on the queue

- Consumer: Reads messages from the queue and processes them

graph LR

subgraph Producers

P1[Order Service]

P2[User Service]

P3[Payment Service]

end

Q[(Message Queue)]

subgraph Consumers

C1[Email Worker]

C2[Analytics Worker]

C3[Notification Worker]

end

P1 --> Q

P2 --> Q

P3 --> Q

Q --> C1

Q --> C2

Q --> C3

style Q fill:#4a90a4

This pattern is called producer-consumer or point-to-point messaging. One producer sends a message, one consumer receives it.

Publish-Subscribe (Pub/Sub)

Sometimes multiple consumers need the same message. This is where pub/sub comes in.

graph TB

P[Order Service<br/>Publisher]

subgraph "Topic: order.created"

T[Topic/Exchange]

end

subgraph Subscribers

S1[Inventory Service]

S2[Email Service]

S3[Analytics Service]

S4[Fraud Detection]

end

P --> T

T --> S1

T --> S2

T --> S3

T --> S4

style T fill:#5fb878

With pub/sub:

- Publisher doesn’t know (or care) about subscribers

- Each subscriber gets its own copy of the message

- Adding new subscribers requires no changes to the publisher

This is how event-driven architectures work. Services publish events about what happened. Other services subscribe to events they care about.

Message Acknowledgment

What happens when a consumer crashes mid-processing? Without proper acknowledgment, you either:

- Lose the message forever (bad for payments)

- Process it twice (bad for charges)

Queues solve this with acknowledgments (acks):

sequenceDiagram

participant Queue

participant Consumer

Queue->>Consumer: Deliver message

Note over Consumer: Processing...

alt Success

Consumer->>Queue: ACK (done, remove message)

Queue->>Queue: Delete message

else Failure

Consumer->>Queue: NACK (failed, retry)

Queue->>Queue: Keep message, redeliver

end

The message stays in the queue until the consumer explicitly acknowledges it. If the consumer crashes, the queue assumes failure and redelivers to another consumer.

Dead Letter Queues (DLQ)

What if a message keeps failing? Maybe it’s malformed. Maybe it triggers a bug. You don’t want it blocking other messages forever.

Enter the Dead Letter Queue:

graph LR

subgraph "Main Flow"

Q[Main Queue] --> C[Consumer]

end

subgraph "After N retries"

C -->|"Failed 3x"| DLQ[Dead Letter Queue]

end

subgraph "Manual Review"

DLQ --> Alert[Alert Team]

DLQ --> Dashboard[Admin Dashboard]

end

style DLQ fill:#f5a623

After a configurable number of retries, the message moves to the DLQ. This keeps your main queue healthy while preserving problematic messages for investigation.

Real story: A payment processor had a bug where certain currency codes caused JSON parsing to fail. Without a DLQ, those messages would retry forever. With a DLQ, they caught the issue, fixed the bug, and replayed the messages from the DLQ.

Popular Queue Technologies Compared

RabbitMQ

Best for: Traditional message queuing, complex routing, enterprise integration

RabbitMQ implements the AMQP protocol. It’s great when you need sophisticated routing:

Pros:

- Flexible routing with exchanges (direct, topic, fanout, headers)

- Built-in management UI

- Supports multiple protocols (AMQP, MQTT, STOMP)

- Low latency for small messages

Cons:

- Not designed for high throughput log streaming

- Messages are deleted after consumption (not replayable)

- Scaling beyond single cluster is tricky

Use RabbitMQ when: You need complex routing rules, request-reply patterns, or traditional work queue semantics.

Apache Kafka

Best for: High throughput streaming, event sourcing, log aggregation

Kafka isn’t a traditional queue. It’s a distributed commit log. Messages persist and can be replayed.

graph TB

subgraph "Kafka Topic: orders"

P0[Partition 0<br/>Offset: 0,1,2,3...]

P1[Partition 1<br/>Offset: 0,1,2,3...]

P2[Partition 2<br/>Offset: 0,1,2,3...]

end

subgraph "Consumer Group: analytics"

C1[Consumer 1] --> P0

C2[Consumer 2] --> P1

C3[Consumer 3] --> P2

end

subgraph "Consumer Group: email"

C4[Consumer 4] --> P0

C4 --> P1

C4 --> P2

end

style P0 fill:#e3f2fd

style P1 fill:#e8f5e9

style P2 fill:#fff3e0

Pros:

- Incredible throughput (millions of messages/second)

- Messages persist for days/weeks (replayable)

- Multiple consumer groups can read independently

- Ordering guaranteed within partition

Cons:

- Higher latency than RabbitMQ (batching)

- Complex to operate (ZooKeeper dependency, though KRaft mode helps)

- Overkill for simple use cases

Use Kafka when: You need high throughput, event sourcing, stream processing, or multiple teams consuming the same events.

For a deeper dive, check out How Kafka Works.

Amazon SQS

Best for: Simple queuing on AWS, serverless architectures

SQS is a fully managed queue. Zero infrastructure to manage.

graph LR

subgraph "AWS"

Lambda1[Lambda: Order Handler]

SQS[(SQS Queue)]

Lambda2[Lambda: Email Sender]

end

Lambda1 -->|"SendMessage"| SQS

SQS -->|"Trigger"| Lambda2

style SQS fill:#ff9900

Two flavors:

- Standard: Nearly unlimited throughput, at-least-once delivery, best-effort ordering

- FIFO: Exactly-once delivery, strict ordering, but limited to 3,000 messages/second

Pros:

- Zero ops (AWS manages everything)

- Pay per use (no idle costs)

- Native integration with Lambda, SNS, S3

- 14-day message retention

Cons:

- AWS vendor lock-in

- Standard queues don’t guarantee order

- Maximum message size of 256KB

Use SQS when: You’re on AWS and want zero ops, or building serverless with Lambda.

Redis (as a Queue)

Best for: Simple queues, real-time features, when you already have Redis

Redis isn’t a dedicated queue, but Redis Streams provides queue-like functionality.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Producer

redis.xadd('orders', {'order_id': '12345', 'amount': '99.99'})

# Consumer

messages = redis.xread({'orders': '0'}, block=5000)

for message in messages:

process(message)

redis.xack('orders', 'worker-group', message['id'])

Pros:

- Sub-millisecond latency

- Already in your stack (probably)

- Simple to set up

Cons:

- Limited durability (depends on persistence config)

- No sophisticated routing

- Scaling is harder than dedicated systems

Use Redis when: You need simple, fast queuing and Redis is already in your infrastructure.

Real-World Patterns

Pattern 1: Work Queue (Task Distribution)

Distribute work across multiple workers. Classic use case: image processing.

graph LR

API[Upload API] -->|"Process image 123"| Q[(Image Queue)]

Q --> W1[Worker 1<br/>Resize]

Q --> W2[Worker 2<br/>Resize]

Q --> W3[Worker 3<br/>Resize]

W1 --> S3[(S3: Processed)]

W2 --> S3

W3 --> S3

style Q fill:#4a90a4

How Slack does it: When you upload an image, Slack’s API drops a message on a queue. Worker pools pick up messages and generate thumbnails, previews, and virus-scanned copies. The chat UI shows a placeholder until processing completes.

Implementation tips:

- Set visibility timeout longer than processing time

- Use message deduplication to handle retries

- Monitor queue depth to auto-scale workers

Pattern 2: Event-Driven Microservices

Services communicate through events, not direct calls.

graph LR

subgraph Publishers

Order[Order Service]

end

Order -->|OrderCreated| EB

EB[(Event Bus)]

EB --> Payment[Payment Service]

EB --> Inventory[Inventory Service]

EB --> Shipping[Shipping Service]

EB --> Notification[Notification Service]

style EB fill:#5fb878

style Order fill:#e3f2fd

Each service publishes events about what happened. Other services subscribe to events they care about:

graph LR

subgraph "Event Flow"

E1[OrderCreated] --> EB[(Event Bus)]

E2[PaymentCompleted] --> EB

E3[ItemsReserved] --> EB

E4[OrderShipped] --> EB

end

style EB fill:#5fb878

style E1 fill:#e3f2fd

style E2 fill:#e8f5e9

style E3 fill:#fff3e0

style E4 fill:#fce4ec

How Uber works: When you request a ride, the Ride Service publishes a “RideRequested” event. The Matching Service subscribes and finds drivers. The Notification Service subscribes and sends push notifications. The Pricing Service subscribes and locks the fare. Each service is independent.

Benefits:

- Services are loosely coupled

- Easy to add new features (just subscribe to existing events)

- Clear audit trail of what happened

Pattern 3: Request Buffering (Traffic Smoothing)

Protect your database from traffic spikes.

Your database can handle 1,000 writes/second. Black Friday brings 10,000/second. Instead of crashing, the queue absorbs the spike. Workers process at a sustainable rate. Some operations are delayed, but nothing fails.

How Stripe handles webhooks: Your webhook endpoint might be slow or down. Stripe queues webhook events and retries with exponential backoff over 72 hours. Your temporary outage doesn’t mean lost payment notifications.

Pattern 4: Saga Pattern for Distributed Transactions

Need to coordinate actions across services with rollback? Use event choreography.

sequenceDiagram

participant Order as Order Service

participant Queue as Event Queue

participant Payment as Payment Service

participant Inventory as Inventory Service

Order->>Queue: OrderCreated

Queue->>Payment: Process payment

alt Payment Success

Payment->>Queue: PaymentCompleted

Queue->>Inventory: Reserve items

alt Reservation Success

Inventory->>Queue: ItemsReserved

Queue->>Order: Saga Complete

else Reservation Failed

Inventory->>Queue: ReservationFailed

Queue->>Payment: Refund Payment

Queue->>Order: Saga Failed

end

else Payment Failed

Payment->>Queue: PaymentFailed

Queue->>Order: Saga Failed

end

Each service handles its step and publishes the result. If any step fails, compensating actions run to undo previous steps.

For more on this pattern, see Two-Phase Commit.

Pattern 5: CQRS with Event Sourcing

Separate read and write models using events.

graph LR

subgraph Write

CMD[Commands] --> WS[Write Service]

WS --> ES[(Event Store)]

end

ES --> Q[(Queue)]

subgraph Read

Q --> P1[Search Projector]

Q --> P2[Analytics Projector]

Q --> P3[Cache Projector]

end

style Q fill:#4a90a4

style ES fill:#e8f5e9

Events flow through the queue to multiple projectors. Each projector builds an optimized read model for its use case.

Learn more about this in CQRS Design Pattern.

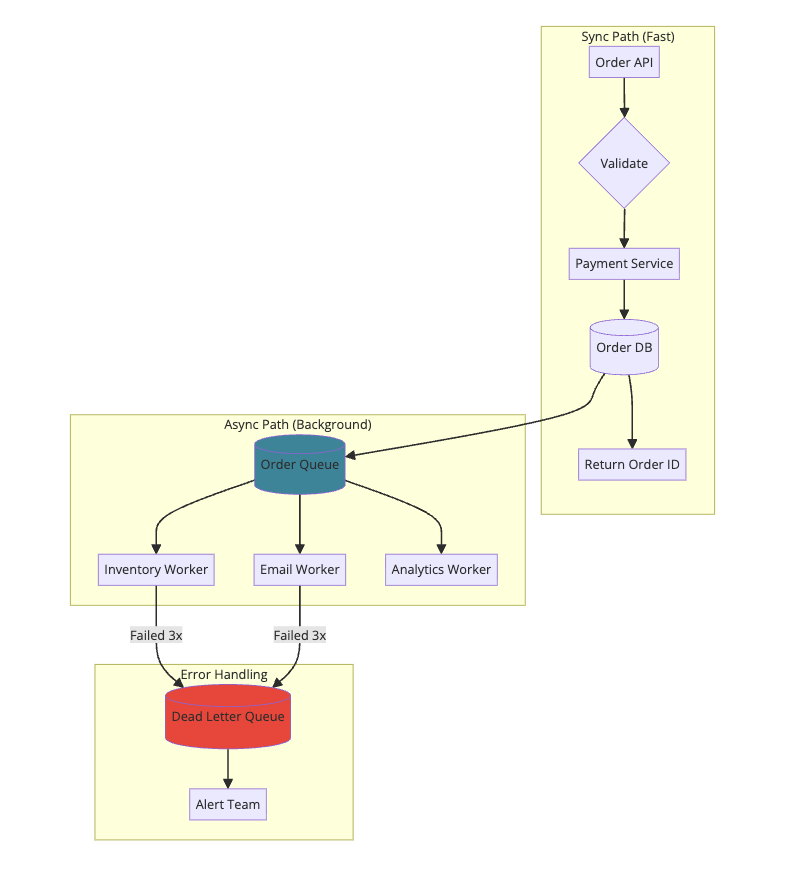

Practical Implementation: Order Processing

Let’s build a simple order processing system with proper queue patterns.

Architecture:

Producer (Order API):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

import json

import boto3

sqs = boto3.client('sqs')

QUEUE_URL = 'https://sqs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/123456789/order-events'

def create_order(order_data):

# Sync: Validate and charge

validate_order(order_data)

payment_result = charge_payment(order_data)

# Sync: Save to database

order = save_order(order_data, payment_result)

# Async: Publish event for background processing

event = {

'event_type': 'OrderCreated',

'order_id': order.id,

'user_id': order.user_id,

'items': order.items,

'total': order.total,

'timestamp': datetime.utcnow().isoformat()

}

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=json.dumps(event),

MessageAttributes={

'EventType': {

'DataType': 'String',

'StringValue': 'OrderCreated'

}

}

)

# Return immediately, don't wait for email/inventory

return {'order_id': order.id, 'status': 'processing'}

Consumer (Email Worker):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

import json

import boto3

sqs = boto3.client('sqs')

QUEUE_URL = 'https://sqs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/123456789/order-events'

DLQ_URL = 'https://sqs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/123456789/order-events-dlq'

def process_messages():

while True:

response = sqs.receive_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MaxNumberOfMessages=10,

WaitTimeSeconds=20, # Long polling

MessageAttributeNames=['All']

)

for message in response.get('Messages', []):

try:

event = json.loads(message['Body'])

# Check if already processed (idempotency)

if is_processed(event['order_id']):

delete_message(message)

continue

# Process the event

send_order_confirmation_email(event)

mark_processed(event['order_id'])

# Acknowledge success

delete_message(message)

except Exception as e:

handle_failure(message, e)

def handle_failure(message, error):

receive_count = int(message.get('ApproximateReceiveCount', 0))

if receive_count >= 3:

# Move to DLQ after 3 retries

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=DLQ_URL,

MessageBody=message['Body'],

MessageAttributes={

'Error': {

'DataType': 'String',

'StringValue': str(error)

},

'OriginalMessageId': {

'DataType': 'String',

'StringValue': message['MessageId']

}

}

)

delete_message(message)

alert_team(f"Message moved to DLQ: {error}")

else:

# Let visibility timeout expire for automatic retry

log_error(f"Processing failed, will retry: {error}")

def delete_message(message):

sqs.delete_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

ReceiptHandle=message['ReceiptHandle']

)

Key Takeaways

-

Queues decouple services. The producer doesn’t wait for the consumer. They scale independently.

-

Use queues for the right reasons: async processing, traffic smoothing, fault isolation, and fan-out messaging.

-

Make consumers idempotent. Messages will be delivered twice. Handle it gracefully.

-

Always have a DLQ. Poison messages shouldn’t block your queue forever.

- Choose the right tool:

- High throughput/replay: Kafka

- Complex routing: RabbitMQ

- Serverless/AWS: SQS

- Simple/fast: Redis Streams

-

Monitor queue depth. If it keeps growing, you have a problem.

- Don’t over-engineer. Start without queues. Add them when you need async processing or are hitting scalability limits.

Want to learn more about distributed systems patterns? Check out the System Design Cheat Sheet for a complete reference, How Kafka Works for log-based messaging, Two-Phase Commit for distributed transactions, and How Stripe Prevents Double Payment for idempotency patterns.

Further Reading: